Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

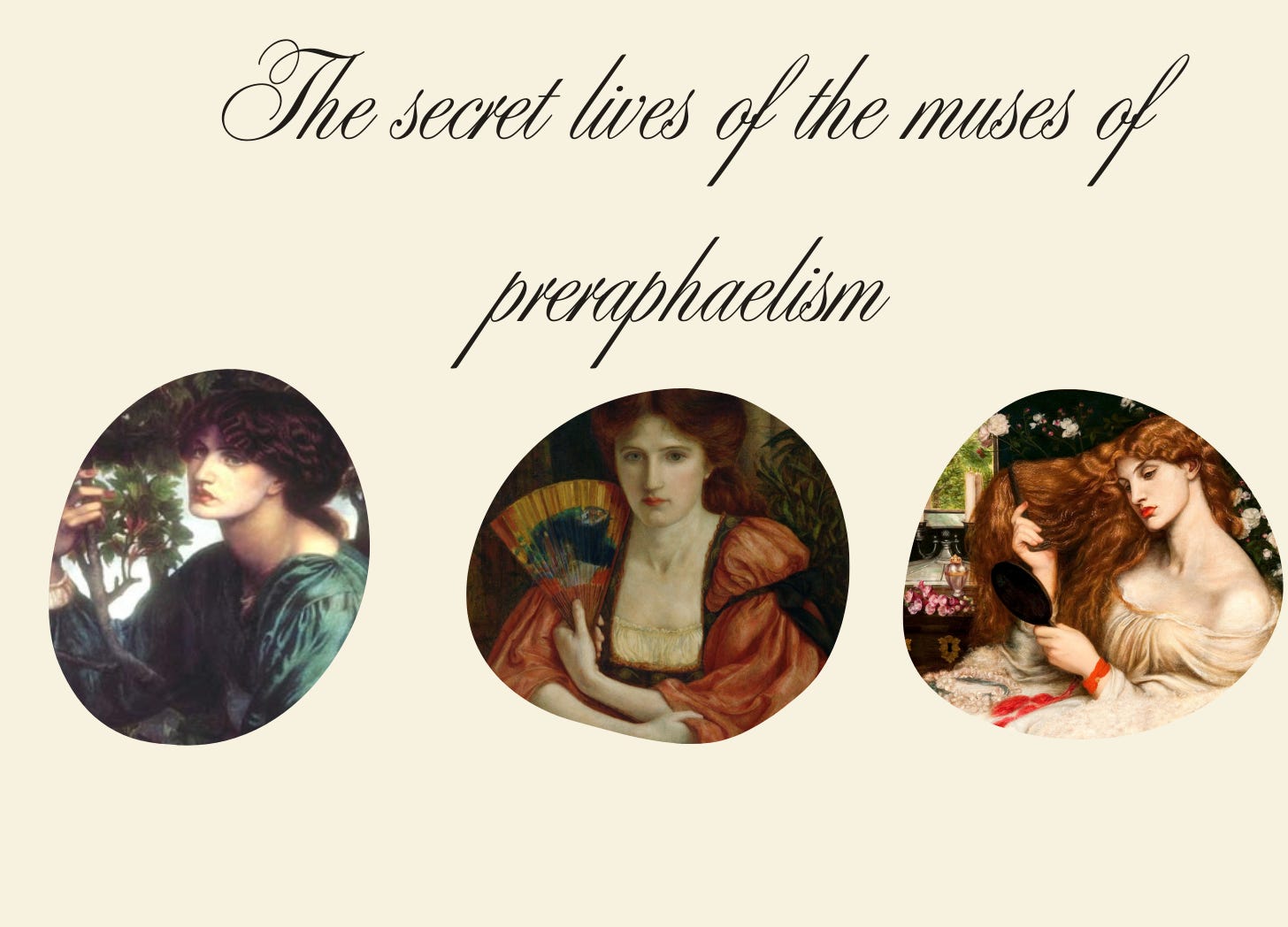

Hello dear listeners, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture. This episode, we’ll talk about the movement of pre-raphaelism and try to unearth the deep and hidden myths about this movement and learn a bit about some of the inspirations and influences that helped the artists of the genre create their art, but more importantly, we’ll talk about the muses and the women that helped shape this movement and the way their careers and art still resonates within art history, and how history often erases the creative output of certain subset of people. I want to bring back to light, if even just a little, the less known women that were at the helm of the pre-raphaelite movement and were thus forgotten by history as usually happens. It is something quite peculiar to witness as some of these women working artists were genuinely extremely successful and well-known in their times, enjoying both critical and financial prosperity, but were quickly forgotten in a generation or two. Sometimes, they were the models and wives of these artists, but also, they were so much more than simply a vision of inspiration to these male artists or a footnote in these men’s lives, they were complex and intriguing persons and very much accomplished artists in their own rights, so, my angels, let’s dig into the secret lives of the muses of the pre-raphaelite movement.

Before we go much further, I think it is important to give an overview of the genesis of pre-raphaelism, the movement of pre-raphaelism is an artistic and literary movement that got its beginning in 1848 by a group of artists who named themselves the Brotherhood of the Pre-Raphaelites which sounds very fancy and ostentatious, this group was comprised of artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, who were all in their early twenties at the time, which by the way, definitely goes to explain the name, and don’t mistake me, I absolutely love it, I just think it’s very cute ! These names will actually end up being mainstays of the British circle of artists in the second half of the 19th century, they will all be very much known and talked about to this day, and be a significant part of 19th century british art history. I have mentioned some of these artists in previous episodes, such as the one on Ophelia in episode three, where we talked about the version of Ophelia that was imagined and depicted by a few of these artists, you can go back to that episode, if you want more details ! The movement of pre-raphaelism was extremely influential and notable, and their significance can still be felt in the way we now think and reflect about art and design. These three early leading members of the Brotherhood were all visual artists, but they were followed by several more artists and even art critics who ended up being part of the Brotherhood. An important part of the group, is its incredible multidisciplinary focus and the versatile way in which art and creativity were celebrated.

The vision of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was one where the concept and the visuals of art were brought back to the age before the industrial revolution and before the classical revival of renaissance, before the age of the great italian artist Raphael, after all it’s in the name isn’t it ? So they were looking to create and manufacture a style of art and craftsmanship to a sensibility that belonged to before the era of Raphael, the renaissance artist, hence the term. The inspiration for their works of art was often taken from the late medieval and early renaissance art of the 14th and 15th century, which are absolutely so lovely in my opinion. I think there is something to be said here about how arbitrary and groundless the ways of delineating and dividing time can be, we want to order and classify things so badly, like oh boy do I know it, especially as a working archivist, I do love to classify things, however when it comes to eras and history, all of it is so subjective and weirdly intuitive. We want to be able to pretend that time works in very clear-cut ways, when it is not the case at all, and movements and artistic styles will overlap and disconnect from each other and sometimes, the period of transition between one to the other is the most fascinating one of all. The renaissance, for example, often is being used as a decisive moment of change and transition, however, this change is not as definitive as you think, the world at that time was still a continuity of the medieval age, and the perspective that those years were a complete age of darkness and that were only saved by the shining light of the Italian renaissance, a time of progress and intellectualism, but what is called the Renaissance designate mostly a very specific occurence at a very specific part of the world, in Florence, Italy. And so, nothing is ever as simple as it seems.

However, it is during that era before the age of Raphael that was the inspiration and the onset of the Brotherhood, their art being thus in dialogue not only with their own contemporary society, but with the past and their vision of the past and the myths that constructed it. Their art was also a continuity of identity, personality and emotion in a way that was not previously. It is the fundamental understanding of what is art and the way people would relate to it that had entirely changed in the passage from the 18th century to the 19th century, where art was simply seen as a profession and a craft, to the 19th century, where, with the Romantics, the perception of art started to evolve into the sentimental and subjective statement of an artist, and so, by the midpoint of the 19th century, that idea of art as a pure expression of emotion and inspiration had taken hold into the imagination, even though it was still quite revolutionary.

That attitude to art and culture was still fairly radical in the light of the official artistic institutions, and their strict interpretation of art. The Brotherhood of Pre-Raphaelism was in opposition to this remnant of the neoclassical era and that was continuing to be enforced by the British Royal Academy of Arts, an institution that instated an extremely rigid idea of the way art should be made and understood. It was not about the creative instinct and artistic feelings where the heart and the inspiration of the artist is the driving force of the art, no, art was more akin to the way we would now consider craftsmanship, there is a place for creativity, but it felt also eminently more practical and pragmatic as an approach. And to be honest, this is not something I necessarily bemoan, because I do think that all craftspeople are artists and all artists are craftspeople and it feels silly to create such a intransigent line between the two.

The thing with those artistic institutions in the 18th century, is that there was a strong theory of what kind of art you could make, which subjects were acceptable and which were not. The world of fine arts was regulated and under the control of the academy, the salons, and the pressure of the moral norms of the period. Being an artist was not seen as being a creative soul, but more so as a craftsman, who had skill and talent, but was trying to create something that was pleasing and to the good taste of the audience. So, while there were such movements as the romantics and the gothic romance that were emerging toward the end of the 18th century, the art and aesthetic of the mainstream culture was still very much one that revered the neoclassical and preferred a very structured and hierarchical understanding of the arts. There was a certain way to create art that was Correct and Right, which left very little place to spontaneity and feelings. In the west, it was thus a remnant of the Enlightenment and of the age of Reason, everything was standardized and normalized, even the paintings in themselves were ranked in a very specific order called the hierarchy of genres, from history painting at the top of the pyramid, which was about historical, mythological or religious events all the way down to the still life painters at the bottom. It is that extremely regimented world of art that made it so that the 19th century brought that entirely opposed reaction and way of thinking. After all, styles and trends are always a pendulum that keeps swinging faster and faster.

The Brotherhood in itself did not last long, it was active and endured only for a short period of five years, however these five years were rich in art, literature and creativity, this group as well as the artists who were in the periphery of that movement continued to influence heavily the world of art and design in the United Kingdom in this second half of the 19th century and beyond. There are a lot of movements that can still have the remnants of the influence of their vision of art and literature and it can be still seen in some ways, more than a hundred and fifty years later. From movements such as the arts and crafts to the way it influenced decorative arts and interior design in the late 19th century, this group of young artists had a more overarching influence than we might think at first. Indeed, even though the Brotherhood did not last long, there were several artists in the generations that followed that would continue to exist in the same artistic movement and stylistic expression as the original brotherhood.

This movement has such an important connection to literature and poetry, to the art of the words, this was as much a literary movement as it was one that dealt with visual arts and craftsmanship. It was a lifestyle and reflection of the the way they wished to live. It came to be more than a simple style of art, but it was also a new understanding of artistic creativity and the meaning of design and artistry. There was an expansion in the ways art was being understood, something that is extremely important in my opinion. Art should not be as elitist nor as restrictive as it used to be, and the ways we understand what is considered as valuable art is tainted by the notion of social status and prestige, unfortunately the way things should be and how things are, are often quite different. And so, there is a certain yearning of freedom and a loosening of the movements in the ways that the Pre-Raphaelites choose to live, if only in the break and distancing from the fashions of the rigid victorian era that the pre-raphaelite muses opt for in their poses and even their daily lives, their fashion sense was very much influenced by the medieval era, where corsets and shape-wear were non-existent and the silhouette was not shaped by undergarments that molded the body in a specific shape, hence embracing a certain looseness and wildness, especially when contrasted to the very strong dress shape of the mid-19th century, with its corseted bodice and its gigantic crinolined skirt.

Those muses were the models and women that would inspire the artists and painters of the Brotherhood, and leave a lasting impact on the movement and on the art that would be created. Because, after all, what is a muse ? She is often more than a simple model, the muse will be a source of inspiration, but also shape the visual direction of the work of art for the artists. In this specific case, the muses ended up becoming full fledged artists in their own rights, and were the basis of the construction of the pre-raphaelite ideal of beauty and womanhood. The muse, by her influence and effect on these artists is thus also taking significant part in building the core visuals and tenets on which the movement of the pre-raphaelites will be built upon.

These women were chosen on the strength of their beauty and of their physical appeal, however, they very much were part of a new standard of beauty that was going against the accepted codes of fashion, and had oftentimes more charm than mainstream appeal. However, they were women who were used as models and to represent such powerful women and figures of legend and myths such as Cleopatra and Lady Godiva, Circe and Ophelia. They were not considered to be the height of beauty during a time that privileged a rosy healthy glow, dark hair and a soft demeanor as the standard of beauty during the victorian era, specifically in the United Kingdom. The cultural idea of what is considered beautiful is something that shifts and morphs, and most importantly has to always be utterly unattainable. The moment it becomes accessible, the goal posts have to be immediately moved. Also, when I talk about beauty standards, these are very much within the culture, which unfortunately will influences us all, no matter what, however what each of us considers beautiful and attractive and pleasing is so incredibly personal, and I genuinely believe that beauty, whatever that uncatchable quality is, is present in each and everyone of us.

These women, these muses, innovated on victorian dress in a way that was considered as very scandalous for the era. After all, sometimes omitting a corset, or forgoing the general silhouette of the era. Not following the trends seems like a benign thing to us today, after all, not every trends will please you, however I think before our era of trendlessness, there was a general silhouette for each era that every strata of society ascribed to. It was simply the norm, if a high waisted empire line dress was in fashion in England in the 1810, then every single women in the regency era was going to be wearing that kind of dress, from the lowest classes to the highest classes. If you were not, you were distinguishing yourself, and not in a good way, from the rest of the group. The same way that during the 1920s when everyone had their hair bobbed or styled and curled in a way that appeared like it was short, if you showed up with waist length hair and a cinched waist, you were setting yourself apart from society, and it would have been so unfashionable. This is very specific to fashion, this notion of visually belonging to a group, but also to distinguish yourself and assert your individuality. So now that this is basically why the fact that these women were wearing dresses that emulated the medieval ones, mostly while posing and around the painters. And so, more than the demure sensibility of the victorian era, these women often represented those tragic figures and of legend. Of dark sorceresses and queens that would bring terror and wreck mayhem into the heart of the viewer, the wildness of emotions and the mythical energy of medieval stories, the paintings of the pre-raphaelite were often a blend of history, myths and legends and of the medieval romances.

Of course, often times, women who were models and muses, had an ineffable quality to them that wasn’t quantifiable , that thing that people often call charm. Those women were as immensely talented and creative and, in their own ways, almost as influential and definitely as capable as their male counterparts, they were the inspiration in some ways for the movement, being the muses and the models for the male artists. Indeed, most of the beautiful images of the era and the female characters that you see in those well known painting of the pre-raphaelite movement represent these women. but also artists, poets and writers in their own right. From Jane Morris to Lizzie Siddal and Marie Spartali Stillman, these women were subversive in so many ways, and I think its especially interesting to note how the work they did, even though revolutionary, often was not remembered nor studied on the same level as their male counterparts. The names of Gabriel Rossetti and Waterhouse are all thrown around when we think about those artistic movements of the era, but they were heavily supported by these women as partners, artists and muses, whose names are rarely mentioned if not in relationship to these men.

There is an archetype of womanhood that is put in the forefront of this movement, but also of the numerous paintings that were created, not only by the members of the Brotherhood, but also by its successors and the following generations of artists. It is a visual that is easily recognizable, their use of the earthy and jewel tones, the red hair, the pale skin, the extremely long hair which is let loose and flowing. It became an archetype that is still very compelling, it is after all one of the most recognizable symbols and motifs of pre-raphaelite art.

Elizabeth Siddal was a model and a muse, and it would be easy to say that she was THE model. And as most of these women were, she was not necessarily classically beautiful and fitting the beauty standards of the victorian era, but nonetheless had something quite enchanting in the way she appeared that appealed to that almost wild sensibility that the Brotherhood sought, something that felt dangerous and different, and was a reminder of the mystical wildness that they ascribed to the medieval era. It is is that different visual aesthetic from the norm that attracted the painters to these women at first glance, after all. She married Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was one of the premier founders of the brotherhood and in whose art she was forever immortalized. Their marriage was short, lasting only two years until Elizabeth’s death in 1862, at the extremely young age of 32 years old from an overdose of laudanum. She is still known to this day as the world of art’s first supermodel, and many books and articles refer to her as such. She was the model that gave her image to Millais’ Ophelia, which we have talked about in a previous episode of this podcast, and to many of her husband’s paintings as well.

She had professional art training, albeit not as extensive as the male artists of the Brotherhood, since female artists did not have the same access to schooling, nor the right to practise with real life models, because of how scandalous that would be. She nonetheless had a career that created works of art that were in the same artistical and cultural tradition and continuity as the rest of the pre-raphaelites. And so, she was a painter and a fairly good one at that, considering the circumstances. She drew scenes of romance and tragedy set in the medieval era, where the archetypal female character was still very reminiscent of the figure that she helped create herself. She was the original muse and model, the one that truly shaped and constructed the vision of the archetypal pre-raphaelite muse, and the work she did for the Brotherhood was thus two-fold, both constructing the genre as a muse, imbibing the scenes with her own sensibilities, but also as an artist in her own rights I think it is absolutely vital to mention that a lot of these women came from working class backgrounds and had to actually earn their living, they did not correspond to the idea of the refined woman of culture, and had a life experience that aristocrat women did not have . They did not necessarily have those leisure and that ease of living.

The way the poses these women chose to portray in front of the easel guided the end result and was an example of that intrinsic symbiotic relationship between the model and the artist, however those women were more than simple models, they were partners and collaborators and were just as much part of the pre-raphaelites as their male counterparts were, and often were full fledged artists in their own rights. Indeed, the monicker of simple model or muse, such an inactive and passive figure, only existing to be looked at, is a bit of a misnomer in the case of these women who definitely brought their own distinctive flair to the art of modeling through their distinctive ways of being, of dressing themselves and the way they carried themselves through life and art. There is a bit of the art of performance when acting roles of women larger than nature to be modeled and represented as, with costuming and styling the hair a certain way, to bring these figures of legend and fiction to life almost. For these women, identity was almost a work of art in itself, creating yourself up, the way they were curating their style, the wild hair, the strong colors that were reminiscent of nature, the floral patterns, all of these elements that were in keeping with the movement of the pre-raphaelites, and so it was as much a way of life as a continuation of the artistic movement. And those choices they made were as much part as creating and fashioning the visual and artistic identity of pre-raphaelism as the decisions the official members of the Brotherhood were taking.

The reception of the pre-raphaelite works of art was not initially a good one, the artistic style going highly against the flow of the world of art and the mainstream ideas of what beautiful art was, and the models who were used for the paintings were so out of the conventional mold of victorian beauty, that it was simply shocking to the public at first. A lot of these paintings represented women with vibrant red hair, clashing with the common understanding at the time that red hair was something to be hidden away and be ashamed of, and actually changed that perception so much to the point where red and auburn hair became trendy and fashionable in victorian England, an example of the way art can shape and influence cultures and societies.

When I say those women were artists in their own way, I do not simply mean as models to be painted and observed. I will not deny that there are some people who simply have the skills and the talent to create worlds of inspiration through their own body and image, however, I do not think anyone will deny that it is not the same thing as taking an active role into the creation of art. Whether that art is the way one lives, the styling of fashion, or painting, design and embroidery. The passive and inactive role of the muse is one that is offset by the active role of the painter, who is the one who looks, who puts the pencil to paper and create.

However, the fact still remains that being a model is the passive and inactive action of being looked at versus the active and purposeful action that is posed by the artist. And so, they are seen strictly as an object of desire and beauty, instead of the creative young women that they were. And after all, as John Berger put in his seminal book Ways of Seeing : « One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object -- and most particularly an object of vision: a sight. » Which by the way, I think that this book is required reading for anyone who loves art history and wants to try to understand it more, I might even suggest also the 4 episodes docu-series of the same name that Berger filmed in the 1970s and is available easily if you just. … Look for it on youtube, just saying. I haven’t said anything though….

These models subverted the understanding of a passive muse by being active participants in the world of arts in all of their own manners, the modeling was something that was part of their lives, as professional models or by just sometimes sitting for a portrait, however it does not encompasses the whole of what they are, and of their contributions to the arts of the Pre-Raphaelites. They were often named as the Pre-raphaelite sisterhood, a group that was the feminine counterpart to the pre-raphaelite brotherhood, almost acting as a foil to them.

Jane Morris would go on to become the wife of William Morris and was a frequent model of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with whom she might or might not have had an affair or several. She was once again an atypical sort of beauty, with strong features and wild hair, she was the face of Rossetti’s Proserpine in 1874, a work of art that is very recognizable. She was also from a poor working class background and had a very keen intelligence and once she had access to knowledge, she learned so much, even teaching herself several languages. She was also an artist, but her artistic practice was within the realm of textile arts, a discipline still too often dismissed, as well as the arts of homemaking. Her embroidery and her textile arts went on to become patterns and designs for Morris & Co.

The Pre-Raphaelites movement had a focus on arts but also on craft, and a perspective that makes them both artistically equal to one another. From ceramics, embroidery, weaving and patterns, the line between what is considered art, and I am talking about Art with a capital A here, and what is considered crafts, design or simply is a very thin one, and while the delineation of what was what was extremely clear in the 18th century and prior, where art was considered to be the oil paintings and the sculptures and the huge portraits and nothing much else, once again, this is also a very western centric and exclusionary definition of art. Because on top of also ignoring the contribution of illustrators, watercolor artists, embroiderers, etc., it ignores the works of art of non-western artists whose practice would diverge from western artistic tradition. It keeps the world of arts to a select few and continues to perpetuate the idea that any legitimate and correct art is created by the white western elite.

What I think is kinda funny, is how much, the more things change and the more they stay the same. I always feel like I hear about people complaining about change and the way modern life is being meaningless and how the modern world is impersonal and corrupting, and I was watching a 1992 British sitcom, where they said a similar line, and I just thought to myself, from roughly 30 years in the future, oh buddy you haven’t seen anything yet. And still, this sentiment seems to come back no matter when you position yourself in history. I do have to think that it probably is stronger at times, but I do think this sense of bitterness toward the way the modern world alienates us is something that is universal across time and space. The pre-raphaelites were disillusioned with the modern world and wanted to look back to the past, and so did the romantics, and so did the neo-classical and, I think, it is by looking to the past that we are moving toward the future. After all, this fascination with the past tells us more about them than it does about the epoch they are looking back to, because it is through the lense of the present that the past is being distorted through, and even though the Pre-Raphaelites were trying to recreate a vague sense of the middle-ages in the way they understood it, through the paintings, through their literature and their designs, those works of art reflect only an idealized and unspoiled interpretation of that era, that had nothing to do with the reality.

Marie Spartali Stillman was from the next generation of artists that were incredibly influenced by the movement and was also a model, and posed for some Pre-Raphaelites artists as well as some photographs, dressed as historical figures of yore, and she looked the part, slightly wild and long haired, with extremely expressive eyes. And while she was very beautiful, it is her art that left a mark, she was an extremely talented artist whose paintings fall within the Pre-Raphaelite artistic style, with beautiful shades of ocre and greens, they have an innate graveness and visual warmth to them that echoes the gravitas of the tragic medieval stories that inspired the movement. She kept the style and movement alive during the later years of the 19th century and is a proof of how even though the movement of Pre-Raphaelism truly was contained to the middle of the 19th century, art history and art styles spill over and sometimes you just fall in love with a specific style, and will keep creating art in that vein well over the trend is over and gone with.

It is a visual style that still appeals, after all Florence Welch from Florence + The Machine uses it as a major inspiration for her visual aesthetic and her albums. There is something about a free flowing dress and wild hair in the wind that still very much captures the imagination of people. I think because even now, we need to sometimes go back to the past and listen the echo of an era where things were magical and where emotions felt grand.

On this, my darling listeners, thank you for listening to this episode of Imaginarium, I hope it was fun and we’ll meet again next month for a new episode and a new deep dive into another lesser known subject of art history and visual culture. If you want to support this podcast, you can do so on patreon @ patreon.com/nadjah. Otherwise, talk about it to anyone you’ll think will like it. And as the youtubers say, like and subscribe, and give us a good rating if you enjoyed. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you again very soon.