The Racim Brothers : Masters of Algerian Ornementalism

IMAGINARIUM : An Alternate History of Art

Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

Hello dear listeners, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture. In today’s episode, we’re going to talk about the art of ornamentalism and miniatures in Algerian art and the cultural impact of Mohamed Racim and Omar Racim, who were significant Algerian artists in their times, and to this day. We will explore how the context of the late 19th century and the early 20th century in the Algiers of a colonized Algeria affected the world of arts and the artistic practice of the artists. In a time of colonization, the importance of traditional arts and craftsmanship, as well and protection of one’s culture becomes more important than ever. There is a conscious effort to protect, but also to revitalize Algerian art and culture from the consequences of imperialism.

Of course, this phenomenon is not unique to Algeria, in fact, even though I would say that most cultures and countries do try to valorize and promote their history and past, however I think there is a special signification to this act being done by former colonies and people who have lived through a heavy history of oppression and repression and whose history has suffered from a conscious effort of being erased, or at least, hugely devalued in favor of a cultural hegemony that would place the imperial power in a position of superiority and strength, so the simple act of preserving, learning and sharing becomes one that is fraught with meaning. When it comes to Algerian art, as an Algerian art historian, I always want to acknowledge the depths of suffering and pain imperialism creates and how those scars still influences the lives of people in Algeria today, because it st ill does, in many ways. However, I think, even more important than the pain, is the talent, the joy, and the pride that one can have in one’s national heritage .

All of this to say Tahia Djazair and let’s dive in, my darlings !

The late 19th century and the early 20th century were a fraught period in Algeria, as it was everywhere I think, as this period is definitely one of transition, with the rapidly changing times and the coming of modernity and the way the tensions between past, present and future created a world of possibilities within. It is one of my favorite periods in history, because I think those years from roughly 1880 to 1940 are ones where everything and everywhere just starts moving and changing irreversibly, where we truly go from the traditional world to what we now consider the modern age, and it is in those years that it all played out, and it is absolutely fascinating to see how it reflects in the arts and the culture. However, living this period while under the rule of a foreign power adds so much more tension to an era that is already one that is fraught with change and extremely rapid technological progress all over the world. The colonization of Algeria started in 1830, after the event of the fan which is when the Dey of Al-Djazair, Al-Djazair being both the name of the city and of the country, after all the name of Algeria is what the french occupation named it, and the Dey is the title given to the sovereign of the Algiers Regency, and tired of the way the french were delaying their debt payment toward Algiers, shooed away the french consul, and this event is what gave an excuse to the french to go on the offensive, after all, Al-Djazair was a rich country full of natural resources, and the coffers of the french were empty. And so, after this, followed 132 years of violent colonization, which were only stopped after a violent war of revolution and independence. I do want to put here, that even though I do not condone violence, I think that standing up to injustice is not violence, it’s simply what needs to be done. The real violence here was the cruelty of imperialism.

Imperialism is a poison that taints the pages of our history, and yet, as an Algerian art historian, I wish for it to not be the way Algerian history is remembered. It was extremely important and an event that shaped the march of history and the way we approach history and I will never minimize its impact and violence that is still being felt to this day, however, I would love for Algerian art and art history to be a source of joy, of pride, bringing back dignity to the way the art and culture are understood, instead of the way it had been disseminated by the french. It is distressing to see how so much of the history books being written about Algerian history still bring the french colonialism as its primary subject, as if there is nothing more to our history than the time shared with europeans, once again it is the way eurocentrism is still the lens history is seen through. I guess I also am, in a way, but I really want to try and put the emphasis on the Algerian artists, works of art and stylistic movements. There is no way to avoid the presence of the french occupation in this story, but they are not the main characters, even though it is also my goal to show and explain just to what extant the violence and savagery of colonialism is harmful, but imperialism truly is more insidious and sneaky than one might think, it affects the psyche and the culture in such subtle ways, and the wound can be seen in colonized countries for years and years until it can finally heal . I want to first brush a picture of Algeria, and more specifically Algiers the capital, also known as the White City, because of its white walls and buildings. In 1830, had started what will end up being more than 130 years of violent and oppressive colonization, during which active and and often armed resistance to the french regime was the norm. And yet, while those overt and covert movements of resistance and defiance to the colonial regime were still ongoing, by the beginning of the 20th century, life had settled in an established routine for occupied Algeria, ultimately, after 70 years of colonization in 1900, few were alive that still remembered the days before the french took control of the country, even if they were all wishing for the demise of the french regime.

The traditional and indigenous arts of Algeria are hugely influenced not only by Amazigh arts and culture, but the influence of islamic and ottoman culture, creating a very rich, diverse and varied scope of arts, crafts, ceramics, miniatures. The art of the Racim Brothers is very much within the tradition of Islamic Art, albeit done with a North African twist, which makes sense considering they are muslim and coming from a muslim country. Even though the umbrella of islamic art is one that designates a vast and rich grouping of artistic and formal characteristics, however as the muslim world is a wide one, from North Africa to the Middle-East and South East Asia, and European countries such as Bosnia Herzegovina and various muslim communities across the world, so it goes without saying hat each of them will be unique within their own very specific geographical and societal context it fits in. Islamic art in Algeria is very different from islamic art in Indonesia or Russia, and this is what makes it supremely fascinating. When it comes to islamic art, at first glance, it might all look very similar, but that is only if you have a very basic idea of what islamic art is. There are indeed a lot of visual and a common aesthetic sensibility. However, the moment you start looking a tiny bit deeper, you can unravel the complexities and visual subtleties of the islamic world. There are common points after all, in culture and language sometimes, even then, I think very tenuously, everyone knows that arabic is ten languages under a trench coat pretending to be one language, and most of the biggest muslim countries are neither middle-eastern nor speak arabic as their first language, Indonesia, after all is the biggest muslim country and is in Asia. The world of art in Algeria in the beginning of the 20th century is one that exists within the control of the french colonial regime, which means that there is a certain rebellion to resisting and fighting the cultural hegemony of french and western culture and trying to valorize and uplift typically Algerian and traditional arts and cultural heritage, by focusing on the arts of ceramics, calligraphy and miniatures, just to name a few of them. There was a considerate effort that has been made to keep up and preserve the folk arts, and the traditions from the deliberate erasure of those by imperialism.

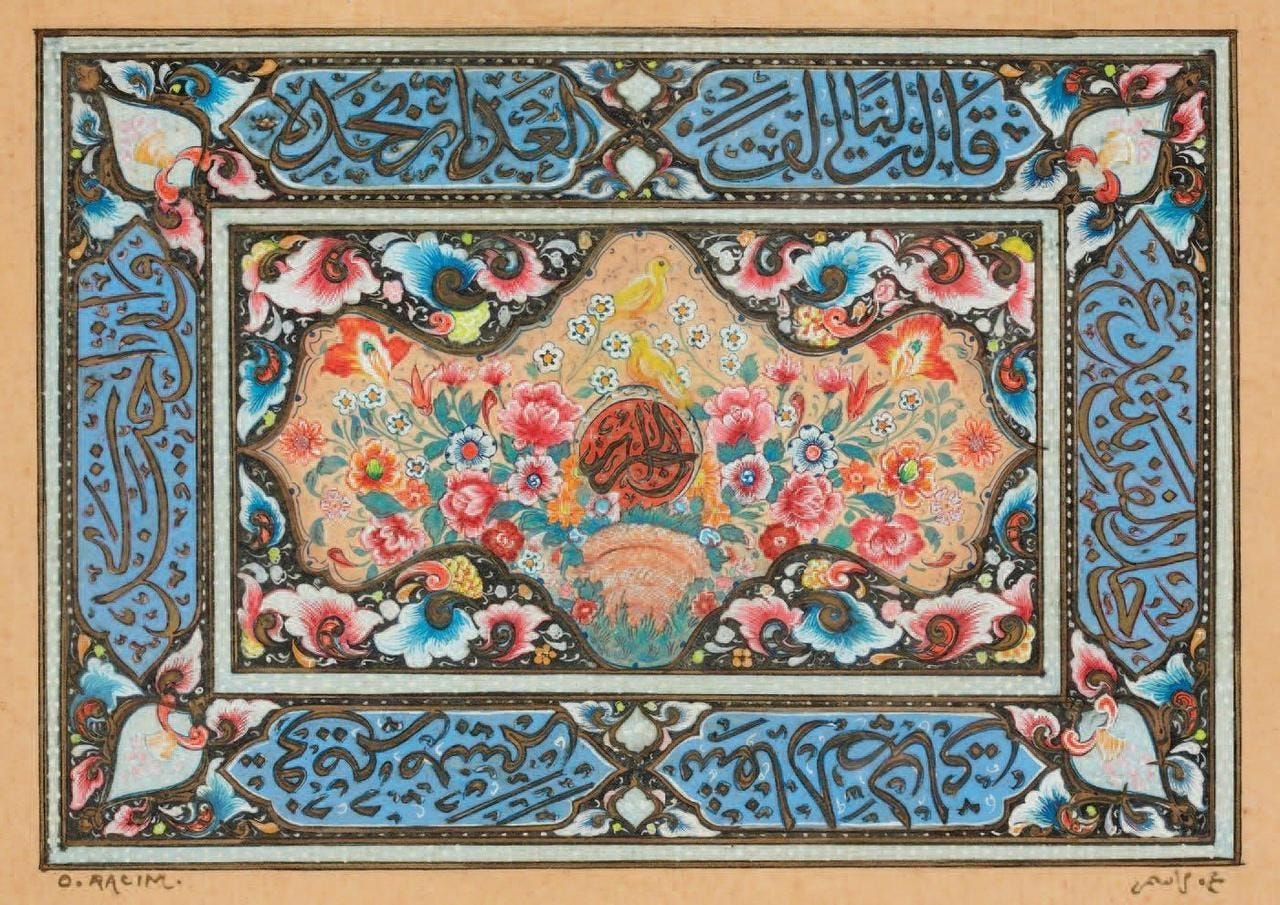

The art of calligraphy has a central place in islamic art, because islamic art was about non-representational imagery for a long time, so no people were pictured in the art, which is why the foundation of islamic art developed a lot around mathematical designs, geometrical patterns and motifs from the natural world. The art of writing becomes integral to visual art, being integrated to works of art, becoming in itself an object of art and beauty. Miniatures and works of ornamentation are pieces that will inform the way we understand and view the Algiers of the past, through the scenes and pictures depicted in miniatures of the early 20th century. I am aware that the name of a miniature already explains it a lot about what a miniature is, however, to explain it a bit, it is a painting or an illustration that is incredibly small and yet complex. There is something so very appealing to miniatures, the scope and scale of the art is so tiny, the details are so meticulous and precise. I personally think there is something so special and peculiar about a piece of art that has an exaggerated sense of scope, either something that is extremely tiny or something that is incredibly big, there is something there at play that interacts with our sense of space, our physicality and self are being thrown out of proportion and we have to really put ourselves in context and the way we feel about existing in contrast to those works of art, it makes us feel conscious of our own physicality. But I do think those tiny paintings are so cute and it’s important to know that while lots of work of arts often exist in a bigger scale and are often more visible and striking, I mean, how often does one goes to a museum and sees a work of art that is several meters by several meters, with a lot of presence and impact, however, we should not discount the discrete and understated ways in which a smaller piece of art can affect us.

Omar Racim and Mohamed Racim were both important pillars of the world of arts in Algiers in the first half of the 20th century, shaping and building the next generations of artists in the traditional arts of calligraphy, painting and illumination, and constructing a community of artists with strong ties to each other, and to the rest of the arab world. These brothers come from a long line of artists and craftsmen who encouraged and trained the young men in the fields of calligraphy, miniatures and painting from a very young age. Their father and uncle, respectively named Ali Ben Said Racim and Mohamed Ben Said Racim, were at the helm of an illumination atelier in the Algerian Casbah, so both brothers were born in an environment that would foster and encourage their artistic talents and skills, and would join the family business as they grew up. I just want to mention, that their family name, Racim, means painter or artist, and is a witness of how that family has been working in arts and craftsmanship for so long.

Born on January 3rd 1884 in the old casbah of Algiers, Omar Racim, the eldest of the Racim brothers, was an ornamentalist, a talented calligraphist as well as a writer, who was very involved in the cultural life of the city in the early 20th century, and was a significant part of the artistic and intellectual circles of Algiers. Omar Racim played a huge role with the Algerian press and his anti-colonial work for the growth of Algerian resistance and fight for its independence. He died in 1959, a few years after the beginning of the Algerian war of independence and a few years short of the independence, and so never got to see the end of the war nor the beginning of independence in 1962, which is somewhat heartbreaking for me. He lived his entire life under the plague of the french occupation, but this is the fate of many who have not lived to see the days where freedom would be gained from the imperialist forces, and who have fought and resisted throughout the duration of the french colonization.

Omar Racim wrote a lot of articles and essays in a few journals and magazines of the times, articles that went talked of the societal issues and were very much pro-resistance and against the occupation of the french. He even founded his own journals, Al Djazair in 1908, Al Farouq in 1913 and Dhou el Fikar in 1913, which got very quickly shut down after only four issues by the french colonial establishment, which tells me they didn’t quite like what he was publishing. Omar even got arrested on November 6th 1915 for his political and nationalist ideas, which were strongly anti-colonial and he was very vocal about them. And I think it’s fun, but also kinda terrible and a testament to the oppressive and repressive actions of the colonial regime, how he kept getting in and out of prison for speaking out about the cruelties of imperialism. He got out of prison in 1921, and continued writing on art, music and architecture.

And yet he did not stop because it was a cause that mattered to him, and fighting for justice is never to be taken lightly. The thing is that, even if the independence would not happen for another 40 years, however, all of those small acts of resistance and of trying to question and fight the fact that the french had dominion over them as an imperial power, all of that is what slowly builds up to the fateful war of independence from 1954 to 1962. People will always try non-violent resistance at first, however, at some point, violence unfortunately becomes the only possible answer, and it will never be as violent as the persecutions and consequences of imperialism.

And so, for Omar Racim, calligraphy and the written word as art are part of his fight against colonialism, but also of his body of work, which is ingratiated in the visual culture of Algiers in the early 20th century, with a lot of commercial graphic design and calligraphy, for storefronts for restaurants and tea rooms, and so his aesthetic touch was an example of the art that was in vogue during that era. I absolutely adore the beautiful advertisement for the restaurant El Bagour, and the ornamentation and intricate details are truly a sight to behold. He has done posters and advertisements for brands and stores, such as the national brand of Hamoud Boualem, which does soda and fizzy drinks, with a beautiful calligraphy describing all the ways in which it will make your life better. I particularly love his series of small views of the city in miniature between 1917 and 1918, mostly from Algiers, but also from Cairo, and the tiny buildings of the city surrounded by beautiful motifs of turquoise, blue and golds are absolutely a marvel to behold, the work and the details are so delicate and exquisite, I do think they are my favorite works of his, however, most of what he created was magnificent.

Omar Racim will open a school in 1939 where he taught miniatures, ornamentalism and calligraphy, teaching and guiding young artists, some of which would go on to become successful artist in their own right, such as Mohamed Temmam. He played a vital role in fostering and furthering the practice of traditional Algerian arts. I also have to mention, but Omar Racim had huge amount of style, I’ll post some pictures on the socials, but the outfits, the tarbouche, the magnificent mustache in his youth, that was one fashionable man.

Born on the 24th of June 1896 in the old Casbah of Algiers , Mohamed Racim was the younger brother of the two siblings, and while both were incredibly successful in the Algerian art scene and in the broader arab and islamic world, Mohamed will be the one who will know the most international success. He exhibited across the world, from Scandinavian countries to countries of the islamic world.His artistic talent was first noticed by Prosper Ricard, who was the inspector of indigenous arts, a job posting that genuinely gives me so much grief, but I guess this is what colonialism was, but the fact that this was a job that was held of course only by french people is just, genuinely kinda upsetting, but you know, whatever, and in 1910, entered au Cabinet de dessin de l’enseignement professionel (the Cabinet of drawing and professional teaching) as a draftsman, which kickstarted what will be a long and flourishing career. In 1919, he was sent to study in Cordoba and Granada in Spain, to learn from the art of of Al-Andalus, and from the golden age of muslim Spain. His early career was spent making illuminations for several books such as Vie du Prophète, or life of the prophet, written by the painter and artist Nessredine Dinet. Nessredine, formerly known as Etienne Dinet, was a french painter who came to Algeria as an orientalist painter, converted to islam and changed his name, which is why, in this podcast we will use the name he chose for himself. He depicted the daily Algerian life in a frank and extremely compassionate and tender way, which is so very contrasting with the way orientalist normally do ply do not want to accept the way he has decided to live his life is absolutely very telling and very obvious, his art is full of heart and soul, it is obvious that he took the time to view the people he drew from a very intimate perspective as he became one of them, instead of the way the orientalists created art from a distance, often as if they were painting unknowable mysterious beings instead of fellow human beings, but that’s the brain-rot that colonialism gives people sometimes.

Mohamed Racim continues to illustrates and decorates books, from the english version of Omar Khayyam by E.G. Browne or the Thousand and One Nights, which was a work that took him eight years, and gave him the time and ressources to travel and visit museums. He won the 1933 Grand Prix Artistique d’Algérie and was the first Algerian artist to do so, which goes to show that the french occupation was overlooking and devaluing the work of the indigenous artists. The Grand Prix Artistique was only won by french artists living in Algeria, colonizers, and not actual algerian artists. And so, the world of art in Algeria was just another reflection of the french occupation. Mohamed Racim’s career continued to go extremely well, he was induced into the Royal Society of miniaturists in England as a honorary member from 1950 onwards, and became a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts of Algiers.

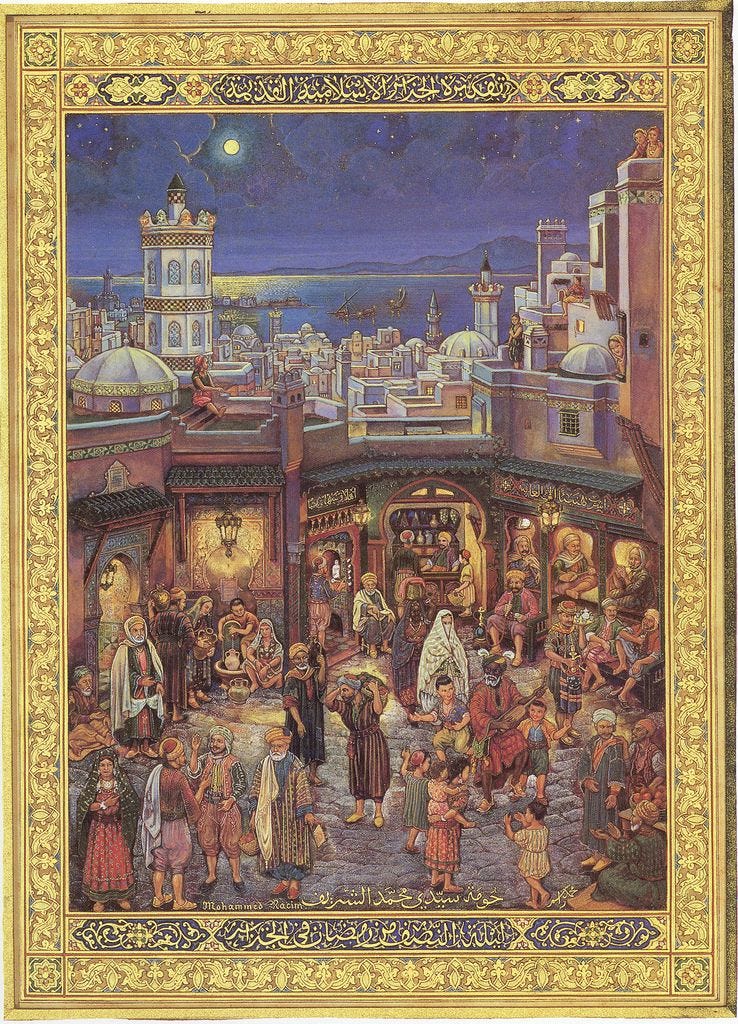

He was defining the image of Algeria abroad with his miniatures depicting scenes from daily Algerian life or from history. Mohamed Racim’s art was a reminiscence of an Algerian society of yesteryear that, even in the first half of the 20th century, had a feeling of a once upon a time that was already long gone by, it was the image of a society and an ideal that was well in the past in the 1930s already. His art was very much reflecting an idea of an Algeria, that could have been, it was dreams of what would never happen under the colonial regime. That idealized and romanticized version of reality was not a real one, after all. The art of the both Mohamed and Omar is an idealized landscape of pre-colonial Algeria, an era that neither of the men had known, and that at the time where they were both adults, was no longer remembered by anyone alive anymore, it had already been generations and the memory of the Algeria that was before the french occupation was now in a distant past. Mohamed has said he wanted to « fix the memory » of this arab and Algerian culture that was deeply changed and broken by the imperial violence of France. However this construction of the past, as a method of resistance but also as a way to reconstruct and rebuild an understanding of a history that has been slowly eroded by imperialism and an oppressive violent regime, was a fantasy, however a fantasy that was needed as a form of cultural resistance.

The seeds of revolution were always planted in the heart of the Algerian fight against french imperialism, there were always trying to fight against the colonial regime, with or without violence, but unfortunately it always leads to violence, because you cannot speak or debate your way out of a colonial enterprise. Revolution is violent as it should be, and it is only in response to an even crueler violence and as Frantz Fanon said in relation to imperialism, and honestly, if you are going to read an author about colonialism and imperialism, make it Frantz Fanon, and make it either The Wretched of the earth or A Dying colonialism, those books were written in 1961 and 1959 respectively in the heart of the independence movement that was sweeping the colonized nations across the globe as they fought to regain their independence from the western powers. And quote “Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well.” unquote. I think this summarizes so efficiently all of the ways imperialism is something that will influences our ways of thinking, our culture and social mores, it is something that is so pervasive and that we need to constantly have to deconstruct within ourselves.

in 1963, Mohamed Racim was part of the exhibit of Algerian painters, an exhibition that took place after the independence of Algeria in 1962, and he took on the role of counselor to the minister of culture, becoming even more entrenched within the artistic community of the city. In 1965, he created a few new stamps, as a sign of a new nationalism, while establishing a new identity to a country that had newly gained its independence. So in a way, Racim continues to take an integral part in the visual and cultural construction of Algerian identity, and I think, it’s important to underline how those three stamps that he made were made to truly valorize and shine a light on Algerian culture. The characters on these stamps are wearing beautiful traditional outfits and surrounded by traditional instruments such as the 3oud or a derbouka, and decorated with traditional tea sets and objects. The art of the miniature is one that goes well with the medium of stamps, with their already reduced canvas and scale, and so it gives itself really well to the talent of Mohamed Racim in making art on a smaller scale. The style of these stamps is evocative of Mohamed Racim’s general oeuvre, with the bright colors, and the decorative calligraphy and patterns. The art of Mohamed Racim is hugely inspired and influenced by the techniques and visuals of the Persian and Mughal paintings and miniatures, and it’s that blend of influences, combined with his knowledge art of calligraphy and miniatures that he was taught in his family atelier in the Casbah of Algiers that created what would become a very identifiable artistic style. The colors are often vibrant and vivid, and he manages to create a distinct visual style that truly puts his north African and Algerian identity in focus, and highlights all of the complexities and refinement that made him an incredibly talented artist . He makes a visible and conscious effort to counteract the influences of orientalist art which were degrading and patronizing, and put forth an image of Algeria that feels true.

Unfortunately, Mohamed Racim died murdered in his house in 1975 in what are still unsolved and mysterious circumstances, however he left and artistic and cultural legacy that cannot be ignored. Most of the collection of his works of art is stored in the museum of fine arts of Algiers, where it is possible to visit and look at his body of work. Art is a form of resistance in an age of colonialism and imperialism, as a form of conscious protestation to an oppressive establishment , and it is important when you are under the control of an empire, to protect and preserve it from erasure and the danger of being integrated into the empire, and so a knowledge of art and history are absolutely primordial to do so. The appreciation and conservation of folk and indigenous art and culture, and the protection of knowledge and the diffusion of that knowledge and the art that was created is just a really good way to broaden the scope of what kind of art is valuable and worth knowing about. A lot of the information I have given you in today’s episode comes from a book I bought the time I was in Algeria during the summer, five years ago, which to this point feels like a lifetime ago. And this book is lush, huge and informative, and I love this initiative to bring to the public accessible information about artists that impacted the world of art concretely. With imperialism, tangible pieces and morsels of history are scattered across the globe, disseminated, sometimes, in Algeria, but most of the time finding their ways in western museums, to be displayed as prized objects, but there is no significant historical and emotional value to those objects being there instead of in their original context, before they were stolen. That lack of context, and that lack of historical significance, truly cheapens the understanding of that art.

There is the example of the skulls of Algerian fighters that are conserved in a french museum, and this just shows you the absolute disregard for people’s humanity and the disrespect and contempt that people still hold. And we need to acknowledge the cruel history and crimes that were committed by the french empire, for which they never made any true reparations from, after all they are just trying to sweep that under the rug and talking about how it is all long gone, but the french independence was in 1962, that is truly not that long ago. And the fact remains that people deserve their dignity, even after their death, and keeping skulls in a museum as a sort of war prize is just another violent crime committed by the french upon their colonies, and now former colonies. Artistic and cultural institution of museums continue to have fraught relationships with the notions of empire, as it is something that has been born out of the Empire, and so the inner workings of those institutions are imbued with imperialism from the inside out. The art world in the way it is set up now, is still a tool for modern imperialism and it is only by dismantling the way we think about artistic and historical preservation, and most importantly the diffusion and exhibition of art, history and culture, that we will be able to find new solutions to the problem of museums and exhibits. When we talk about giving back the artifacts to their countries of origins, I know it is a conversation that continues to be fraught with complications, however, the basis of it all is to give justice, and to right those incredible wrongs that have been committed, and giving back history and culture to those it had been stolen from. It is a good first step, at least I think, and there are more and more instances of countries claiming their historical items back, and I have good hope that the institutions of art and culture will change and evolve for the better in time.

The construction of Algeria’s modern art world was made within the context of the french regime, from Omar Racim and Mohamed Racim to Baya Mahieddine and Mohamed Temmam. Algerian artists were also swept away by modernity and the rapid changes and progress that the early 20th century brought with it, they were trying new techniques and experimenting with art, all the while preserving the traditional practices and cultural influences, to create a blend of something absolutely unique. This is a story whose origin is very much set in the space of the city of Algiers in the heart of the casbah, where two brothers first learned how to paint and how to write beautifully, and this story reflects the beauty and the struggle of a city, of a country.

On this, my darling listeners, thank you for listening to this episode of Imaginarium, I hope it was fun and we’ll meet again next month for a new episode and a new deep dive into another lesser known subject of art history and visual culture. If you want to support this podcast, you can do so on patreon @ patreon.com/nadjah. Otherwise, talk about it to anyone you’ll think will like it. And as the youtubers say, like and subscribe, and give us a good rating if you enjoyed. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you again very soon

.