Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

Hello dear listeners, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture. Today’s episode is going to be an exploration of the way colonialism and orientalism have influenced fashion and fashion illustration through the ages, and the way it still permeates the current fashion culture. With runway shows inspired by the « orient » and Japanese and Arabian and vaguely exotic and quote unquote ethnic aesthetics, the ways orientalism shapes and inspires fashion and designers is alive and well in the fashion landscape. I just want to take the time to thank saffron @ synthetic-pearl, a beauty and fashion critic who suggested this topic to me, so thank you for the lovely idea which led me through some glorious paths of research, which has been extremely fun as usual ! Please check her out, I’ll link her socials in the description and be sure to keep up with wha tever she does !

Of course, this topic is one that is never ending and ever growing, and so this will be only but a snapshot of a very broad theme, and while I will do my utmost best to give a good overview at least of the subject, and the way it is still incredibly relevant, please do forgive me if I can’t touch on every aspect of it. Fashion is something that truly fascinates me, I love clothing and I love beautiful thing and I love well crafted garments, and I think fashion is one of those things that says so much about not only oneself, but also about a certain era, a certain place and a certain culture. It says so much in one glance about people’s perception of themselves, status, and social norms, and this is why for me I absolutely adore fashion as a craft, but also as a reflection of culture, society and mores. Fashion is an art, dress is an art, but also the history of it, the same way as visual art is, says infinitely more about ourselves than we think it does. This subject is an extensive one and could very well be the topic of a many entire book, and has been but we’ll nonetheless try to go as far as we can in this topic together. So let’s begin my loves.

Semiotically speaking, clothing is one of the first, if not the first visual cue that we have that truly conveys certain important hints of cultural and social significance. It is the first element that we see that communicates something to the person who looks at us. Before we even start speaking, the garments we wear and that we have chosen to wear are already saying something about us. The way our clothes communicate and send a message has evolved and slowly but surely morphed through time. The way a black dress used to signify mourning in a certain context, and still does, however this black dress does not have the same meaning depending of the era and the place, after all, in certain regions of the world or religious practices, the use of white symbolizes mourning and death. And so, dress is part of a cultural understanding that we aren’t even necessarily aware that we are taking part in.

Up until roughly the 1990s, anyone who had an office job had to wear a very formal outfit, someone who was the CEO of a company was wearing a complete suit and tie, and would probably never be caught dead in an ensemble that was anything less than extremely polished and this would be worn every day when they were going to work. And this was simply part of the cultural norms that were part of the modern world. However, this signifier of someone’s position, social status and career has morphed through the years, with the rise of business casual, and the way society as a whole becomes less formalized, we can definitely see a shift in the way people have been dressed since that time. And this is not a judgement of value, simply an assessment of the situation at hand. For example, when it comes to the tech industry, you can see men in tee-shirts, jeans and flip flops who are now occupying the top position of the company, and so that formalism that used to exist no longer exists. The power business suits of the 1980s with its gigantic shoulders was a symbol of power and a visually assertive, meanwhile the 21st century tech says that they do not have the time to care about fashion, that they are above that effort and care, and will either be wearing the same thing every day the way Steve Jobs did with his understated black turtleneck, or with the very nerdy college boy aesthetic that a lot of these tech entrepreneur CEOs are wearing, with sweatpants and tee-shirts that seem to need to go into the wash, despite the fact that they are millionaires or billionaires.

So clothing, as much as it is simply a garment that has the primary function of covering your body and a form of self expression, is also a status symbol, and the significance of those status symbols and the shape they take is definitely influenced by the dynamics of a world that is still undeniably based on structures of imperialism and colonialism. Those concepts have shaped our world so thoroughly, that every single facet of the modern world have been influenced by them, in a way or another. In a society where the balance of powers is still based between the colonial power or the colonized nations, a relationship that has been established long ago, and which still is incredibly pertinent. Today, however, the existence of imperialism has taken on a more insidious camouflage. After all, the age of Empire is over. Nonetheless, it is not as true as we wish it were, with the many western military bases across the world, and the use of barely paid labor in poorer non-western countries, I would say that the tenets of imperialism are all alive and well, it is not because it’s not as obvious as it used to be, that it is totally gone, the rules of the game have changed, but the game is still on.

Fashion has been a world where craftsmanship and art has always coexisted hand in hand, and even though the system of fashion the way it currently exists has only been in place since only the 19th century, the beginning of the industrial era truly kickstarting it, at least, in the way it is currently defined, and haut couture being usually defined as being started by Charles Frederick Worth with his House of Worth, even though this particular fact is very much debated, because people have been dressing themselves for ages, so why is it only now that it is being called fashion and haute couture, and everything before that is simply referred as dress or costume history, and the reason why goes very much hand in hand with the industry and capitalism of the time. After all, people have been dressed and clothed for centuries and and centuries before that, and people have always taken care of how they dress and appear, and I think personally, that it is reductive to scale down our understanding of the world of fashion to the way we have been defining it in modern times, after all there is so much more to explore. While clothing and garments beforehand were all hand sewn, bespoke and made to the taste of the client, and the art of sewing and mending was a regular and common occurrence, because clothing and fabric was extremely precious, in a way that we, in our world of disposable fashion, will never be able to understand. And so, it is once that capitalism and industrialism entered the world of garment making, that it suddenly now was Fashion.

Fashion is often considered as art, but it’s not quite, I personally do think fashion is art, I’m very much of the opinion that every creative endeavors can be art whether its a sculpture, an embroidery, a quilt or an oil painting, and of course not limited to those, however, fashion is in a very particular position comparatively to these other artistic fields, because an article of clothing has to be worn to be a piece of clothing, otherwise.. It is really a garment ? Or is it more of a textile sculpture ? Apart from the very specific situation where you are a nudist and you somehow have never worn any clothing in your whole life, every single one of us interacts with the world of fashion. After all, I only have to refer to that absolutely groundbreaking scene in the devil wears prada :

Miranda Priestly : "This stuff"? Oh. Okay. I see. You think this has nothing to do with you. You go to your closet and you select, I don't know, that lumpy blue sweater, for instance, because you're trying to tell the world that you take yourself too seriously to care about what you put on your back. But what you don't know is that that sweater is not just blue, it's not turquoise, it's not lapis, it's actually cerulean. And you're also blithely unaware of the fact that in 2002, Oscar de la Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns. And then I think it was Yves Saint Laurent, wasn't it, who showed cerulean military jackets?

Miranda Priestly : I think we need a jacket here.

Miranda Priestly : And then cerulean quickly showed up in the collections of eight different designers. And then it, uh, filtered down through the department stores, and then trickled on down into some tragic Casual Corner where you, no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin. However, that blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs. And it's sort of comical how you think that you've made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you're wearing the sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room... from a pile of "stuff".

And this scene, which is absolutely iconic, manages to truly captures the fact that even though fashion can seem frivolous and superficial, fashion is something that we are all part of, no matter what. We all wear our little outfits, and if we try to conform with the current trends, that fact says something about us, but if we also try to really navigate our fashion style on the margins, and out of the norms, well this also says something else about us. There is simply no way to opt out of the fashion game, the clothing we choose to wear and not to wear, the way we dress is a way in which we interact with not only ourselves, but the society around us.

The art of garment making has been something extremely important to all societies, and is something that continues to drive commerce and trade today, after all, fashion is one of the biggest industries in the world. Before fashion and dress got altered by industrialization and capitalism, it was one of the most expensive thing you could own, where every single garment take time to create, and labor compensated, and even though the process of making clothing have been sped, they do still all have to be individually made by people. Every piece of clothing that is created is, as of recording of this podcast, continues to be made by a skilled worker. And this is extremely important to understand as we try to ponder all of the way clothing interacts with commerce and art.

Orientalism is a book by Edward Said, an amazing Palestinian author and theorist, published in 1978 that unpacks and unravels all the way the western world interacts with the concept of the Orient, it is a seminal text of cultural critique and so let’s dive deep into 3amo Edward’s writings. Edward Said is the key figure of the post-colonialist analysis, especially with his fundamental book Orientalism, and also I would be remiss to not mention his book Culture and imperialism which are still to this day absolutely essential in understanding the way colonialism, culture, art and the global world intersects. The way othering and fetishizing still plays a significant role in dehumanizing non-western culture and downplay their humanity and skills to the world at large. The orient, as understood in the western imagination is thus a total fabrication that was based on a desire to create have a narrative foil to the western identity, on which to build and frame western culture. And so, our understanding of otherness and the way the image of the oriental is created is a fabricated image, a fictional product of imperialism.

Dress and costume is one of the initial elements that is taken noticed of in ultra awareness of the differences between the west and the orient that orientalism wants to deconstruct, after all, the way we dress is, as said earlier, the first thing we have to confront when facing someone else. The textiles and garments of the ~East are both elements that reinforce the idea of the mystique and the hidden treasures behind the veil that is given as a narrative in western countries, I mean there is only to see how white people discuss veiled women, I’d know as a hijabi myself.

Colonialism and imperialism have always been and continue to be a driving force of fashion, after all, imperialism is a facet of the world exchange, albeit not a voluntary one from both parties, but while the colonial power forces its own cultural hegemony on its colonies, these colonies will also, in turn influence the culture of that colonial culture, or maybe it would be more akin to cultural appropriation in this context. After all a genuine cultural exchange can only happen on the basis of equality and sincerity. When there is a power imbalance as one in an imperialist nation with its colonies, that genuine exchange of culture, knowledge and art simply disappears, and it can easily turn into cultural violence.

After all, one only has to look a the history of indian textile and garment making production to understand the horror and the ways imperialism have shaped that industry, and the way the western idea of the orient and of the beautiful oriental and indian textiles that was hidden away in the indian subcontinent. There is only to think about the world of muslin and chintz and damask, and once you lift that curtain, you discover that fashion can be a world of unseen violence. Because after all, so many beautiful things have an ugly story. The history of dhaka muslin is one such story, that is absolutely tragic in its cruelty, and its consequences both for the people who suffered through it most importantly, but also for the loss of culture, and of the techniques that had been perfected for centuries. This muslin that was made in what is now Bangladesh, but back then was called bengal, was made through an extremely elaborate process that had up to sixteen steps and used an extremely rare cotton that only grew on the banks of the meghna river. Once again, I want to remind everyone that cloth back then was extremely valuable and this type of muslin, that was extremely time consuming and demanded very meticulous and skilled labor was even more so.

The cloth was apparently so fine, delicate and transparent that it was nicknamed « woven air », and those fabrics that were bought by the english, and so this fabric that was used to create form saris was now used to sew those late Georgian era dresses that were inspired by the classical silhouette of Ancient Greece, and these fabrics were so translucent that they were considered as racy, and were caricatured in the journals of the times. So, from the 1790s to roughly the 1810s, so the Jane Austen Period for the intellectuals in the chat, European fashion was mostly influenced by classical fashion, by that draped look and translucent look inspired by ancient greek and roman statues. Muslin was the fabric of choice for these late Georgian dresses, and the exquisite and extremely expensive dhaka muslin was the one that the higher classes went to. However, this specific type of muslin that required the highest of specialized skills, and were made only in certain specific Bengali villages, When it comes to dhaka muslin, it is important to understand that while current muslin has a thread count of 40-80, that version of muslin that existed so long ago, had a 800 to 1200 thread count. So the quality of this cloth is just so incredibly fine and superior to anything that is currently being made, when it comes to muslin.

The technique with which this fabric was created simply. Disappeared. And by the 20th century, the only remaining specimens of this particular type of muslin were the ones found in museums. Basically, what happened, is a pure destruction of the trade of dhaka muslin by the East India Company in the late 18th century, by controlling the whole process and exploiting the workers by paying them less and putting them into debt, and then the British began to create muslin of their own at a way cheaper price, and cheaper quality, thus destroying for good the Bengali trade. And so, imperialism leads to an erasure of history but also of skills and knowledge, and shrinking the financial independence of non-western craftsmen. This was extreme targeted violence in all ways possible. I think at least, this one story has a bit of a happy ending, as Bengali initiatives are being taken to bring back those long forgotten techniques and fabrics with a lot of success.

There is that portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress by Thomas Phillips in 1813, in that one portrait, but not only him, a lot of British aristocrats and upperclass people who could afford to commission a painting were being painted and represented in exotic vaguely oriental garb, I admit feeling a bit stumped at what they seemingly wanted to communicate, maybe a sense of fantasy and exoticism, or maybe some worldliness ? or maybe they simply thought it looked kind of cool, which it does. I mean it doesn’t make what they did any kind of right, but it is just a proof after all, of the global reach of the British Empire, that these types of garments, fabrics, and quote unquote aesthetics were being brought from the corners of the Empire to the headquarters of the British isles. This was simply a mirror reflection of Empire, after all. The Kashmiri shawl is yet another example of this dialogue between the empire and its colonies, of a garment that became a status of symbol and of wealth in the UK, but only on the back of exploited and colonized workers.

A while back, I have read an article about french fashion being inspired by Algerian traditional garments and techniques such as the fetla, the traditional embroidery of gold thread and the shape of the vest of the Karako. I will link this article either in the description down below, or on the social media platforms I am on. This article is in french, however, it is yet another facet of french colonialism, but one that is more insidious than the obvious consequences and violent cruelties of imperialism. Orientalism and the profiteering of ethnical symbols and cultural traditions and craftsmanship is just yet another way that erases the contribution and complexities of colonized countries culture and past, and ends up flattening them into a one dimensional and simplistic understanding of that culture and this is how orientalism often works, by simplifying the other culture in one that is both mysterious and unfathomable, draped in silks and smoke, and yet these people are also barbarian and backwards, and need the actual civilized white people to teach them how. Imperialism and orientalism makes it that these two statements are true at once.

And once you strip a people out of its culture, you then sell it back to them. (Capitalism is simply an advanced form of colonialism)

This kind of cultural appropriation strips those symbols and motifs of their cultural significance to those that it matters to and is reduced to a simple visual artifact. It becomes a relic of something maybe mysterious and unknown, but otherwise empty and devoid of any significant true meaning. I want to be clear that when i talk about orientalism, it is not necessarily a judgement in value, albeit, maybe. a tiny bit. But it is mostly simply an objective phenomenon that can be analyzed, understood and comprehended within the global socio-historical context, however I do think it is important to acknowledge that cultural exchanges and sharing happen in a very organic and respectful and thoughtful way. However, this cannot happen when the relationships of powers are so unbalanced.

It's important to remember that so many of the textile terms and vocabulary comes from non-western languages. Culture and words and language travel, but it is interesting how so many of the textile terms come from othered cultures, from muslin to silk and taffetas and cashmere, There is something about the grandiose and perceived mystery and luxurious of the east that is extremely attractive, until it loses its luster, and becomes a normal and commonplace part of fashion and material culture. After all, paisley has lost all of its cultural meaning and is now only one of those 1970s-ish patterns, when it was originally a pattern created in the Kingdom of Kashmir during the 16th century, and is now ubiquitous for new age moms.

And so, the presence of orientalism in the world of dress and fashion is extremely pervasive. It’s important, once again, to understand that orientalism as the way the West, once again quote unquote on that word, distinguishes itself and creates its own identity and culture by othering the East. Therefore, there is also a dimension of appropriating the culture of the Other and making it theirs, to further establish the western identity, contrasting it to an identity that they could use and discard, much as a costume or a meaningless accessory.The aesthetic of the ancient east, once again, quote unquote, was an definite inspiration and source of creativity in European dress and art in the late 19th century, after the opening up of Japan’s borders to the western world in 1853, which by the way I will mention that it wasn’t done willingly, but because it was forced by the Americans. Unsurprising is all I will say.

And so, the era of japonism et chinoiseries in the late 19th century influenced art in a major way in the western world, after all, notorious artists such as Claude Monet and Van Gogh were deeply influenced by Japanese prints, but this influence went to the world of decor and fashion as well. Paintings of women in relaxed poses and dresses that are going against the extremely rigid fashion of the era, often wearing kimonos, or garments very reminiscent of it, often in their own homes, in lounging poses that feel decadent and slightly debauched, and I do think there is something of the seductive and dangerous orient to it all. And so, this influence of the Japanese kimono, less restrictive on the body can be seen in several works of art of the last two decades of the 19th century as well as in the beginning of the 20th century. This coincides with the dress reform movement of the late 19th century that wanted to suggest more comfortable clothing and to loosen up the victorian silhouettes, as a form of emancipation from what they considered a very restrictive form of garment.

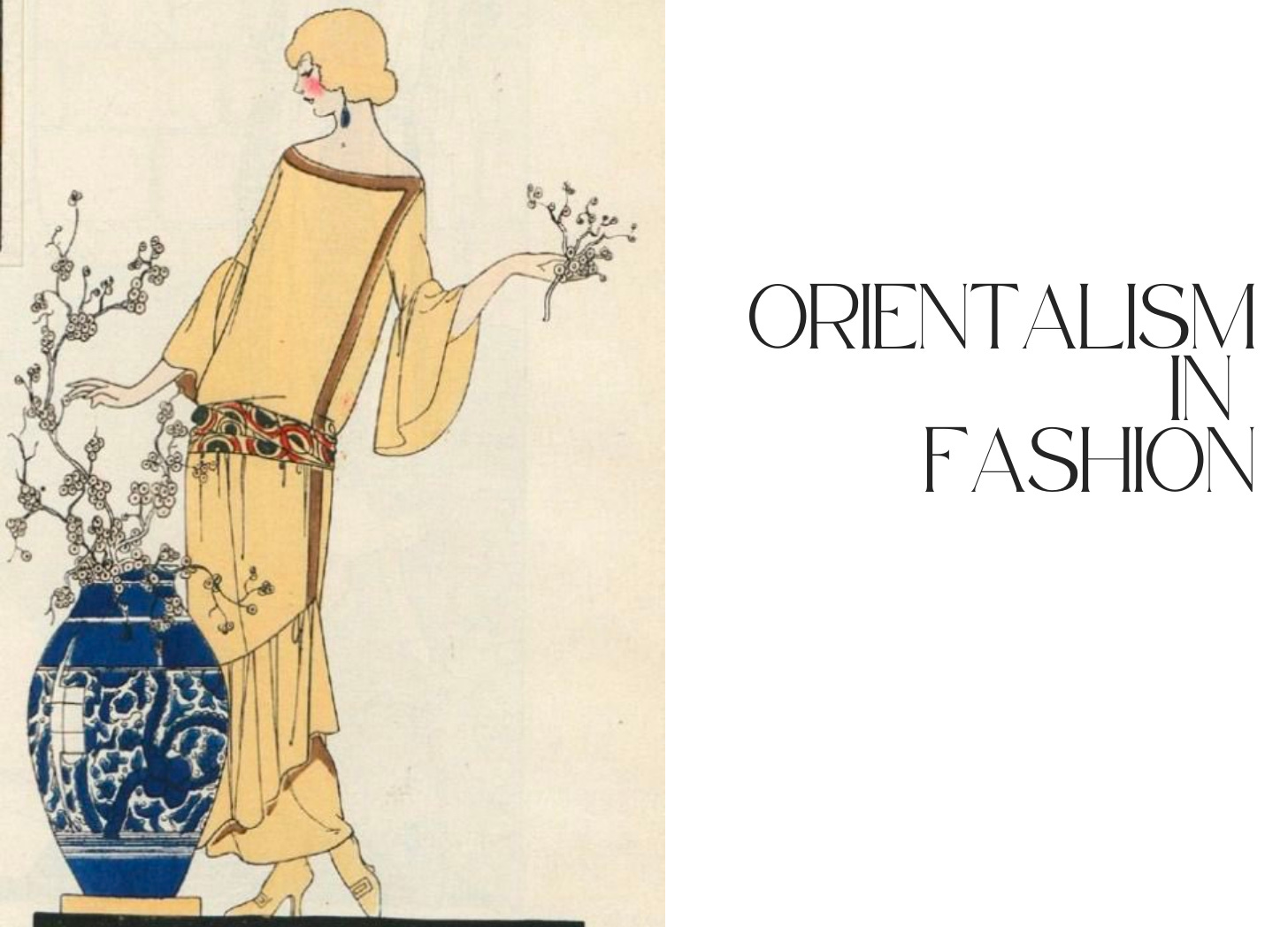

In the 1920s, orientalism was an extremely prevalent influence on fashion, I have talked about it a bit more in the third episode of the second season : Art nouveau & art déco, an early 20th century affair, where I do discuss and introduce this subject already. And so, in the 1920s, an era that was extremely influenced by especially the in interest in the orient that was in vogue during the era, from the east asian influences to the quote unquote arabian influences, the inspiration from foreign locales was unmistakeable on the fashion creation of the 1920s. Paul Poiret, a french couturier of the early 20th century, was extremely popular and his designs were hugely inspired by visions of the East, using foreign fabrics in his creations.

This is also the era that saw the rise of egyptology and the fascination for ancient Egypt, which had a huge cultural impact on western society as a whole. As much as you can say that archeology was for the rise of knowledge, there is a good chunk of imperialism and colonialism in this, after all, so much of that field was developed by western academics in non-western countries, after all, Egypt was a British colony in that time, and so, the relationship of powers is one that is extremely uneven. And there is something a bit perverse about the way imperialism advances that non-western countries cannot unearth and study their own history as well as the argument often being given that well, western academics and researchers simply know better and have better ressources, while ignoring the reason that western countries have more money and resources is because they got it on the back of their colonies due to the imperial project. And it is wild to me to ignore all the physical work and labour by indigenous people on those dig sites, and how often, it is due to the knowledge of these people that these digs and discoveries even happened. This is an argument that is also often given when western museums refuse to give back artefacts to their countries of origins, and if those institutions were truly and sincerely dedicated to the cause of decolonizing museums and cultural establishments, more concrete actions would be taken, instead of perpetual lip service.

When it comes to clothing, after all, they communicate a very specific message and while I think that there is space to subvert and overturn those meanings, there are certain implications that I think are important to think about. I do prefer to assume good faith in people, however as much as people do like to say vintage aesthetics and not vintage values, which is a statement i generally agree with and I hugely love thrifting and shopping for vintage clothing, it is a sustainable way of buying clothing after all. And wearing vintage clothing does not signify that you have traditional or conservative politics and ideas. But the concept of wearing specifically 1920s colonial adjacent clothing on an archeological dig in Egypt, knowing all of that history, to me, there is something so callous and insensitive about it, and honestly I just think wearing clothing reminiscent of the colonial archeological enterprise in Egypt to go work on archeological digs and perpetuating this project while you are an American is just pea-brained behavior.

The history of Ancient Egypt definitely is part of orientalist aesthetics, even if it is not an orientalism that targets a living culture, however the way people depict the Romans and the ancient Greeks vs the oh so mysterious Egyptians is very telling. It is only them that have that sort of mystical and arcane treatment applied to them in the cultural narrative, unlike ancient Greece and Rome whose history and records are being treated in a more rational and historical manner, there seems to be an added touch of the mystery and the occult in the perception of ancient Egypt.

During the past few decades, especially during the 90s and the 00s, there is a definite presence of runway fashion shows and photography editorials in haute couture that are « arabian » themed or « asian » themed, and were absolutely ludicrous, even though I have to admit that the fashion industry has gotten more sensitive to these issues in the past few years, there is so much work still to be done, and not enough reckoning with those specific collections, especially if they were created by beloved designers. I will say that even though I fully believe it is because the subject of diversity and inclusion has been a popular one and relevant one in the mainstream conversation. I am maybe a bit cynical but I can’t help but feel that if these issues were out of fashion, the industry will definitely go back to making exotic themed photoshoots again. Using a certain culture or ethnicity as a basis for an aesthetic or costume, without understanding any of the real significance behind it, is not a genuine cultural exchange, but simple cultural appropriation.

The 1997 fall and winter christian Dior by john Galliano was called the geisha collection, which is ironic considering it’s not even inspired by Japanese geishas, but by chinese fashion, and yet, this is what orientalism do, it flattens all kinds of different cultures, regional differences and particularities into one single idea of what the Vague « East » is. This concept, as much as being harmful, is unhelpful aesthetically and historically speaking as well, because it simplifies the complexities and beauty of non-western culture for the profit of capitalism.

In the past few years, there has been a significant use in fashion of such symbols as Hand of Fatima, the Nazar, the Yin and Yang. These motifs have been used from high fashion runways to fast fashion, and have become almost ubiquitous. Faith and spirituality are incredibly personal and intimate, but I do think there is something to be said about the use of spiritual imagery in a world taht feels devoid of spirituality and maybe to counter-attack the emptiness of modern capitalist society using those spiritual and religious symbols. Of course, there is something to be said about these symbols being foreign to the western world, this is simply an extension of orientalism, and the construction of a western mostly christian, slightly atheist identity, in contrast to what they perceive to be the mystical and esoteric foreign Other. Foreign, and once again, using this term with huge quotes around it, because foreign to who ? The concept of foreignness is also one to be deconstructed, because once again, the question is always compared to who ? It is always depending on the perspective that is being seen. It is a question of who is considered to be the basis of neutrality ? Everything is subjective, and thus, even our notion of neutrality in scientific research are biased in one way or another, and so, the methodological research in art history can also be. It is important to deconstruct those patterns of thoughts and always try to understand what is the perspective and what is being looked at.

Using these symbols as simple patterns and motifs, without acknowledging at least their spiritual and cultural significance simply feels like a shallow pastiche of meaning and substance.Those accessories and collections want to have a feeling of real feeling and connectedness with the universe, and want to make it seem authentic and not as empty and shallow as it is, in the end.

Fashion is an enduring physical remain of empire and the consequences of it continue to burn in our psyche to this day. After all if fashion is so intertwined with imperialism and capitalism, and fashion is a field that is essential to be able to understand culture, our interpersonal interactions and our social mores, then surely it means that the presence of empire is still felt in our everyday lives, as a potent reminder of the cruelty that has been committed and continues to be committed, and the blood that has been shed on the altar of beautiful things and beautiful fashion. Orientalism is part of the past and current western fashion world, through colonization and imperialism, to a point where certain fabrics, cuts and garments that were intrinsically part of a certain cultural have been assimilated and are now ubiquitous in fashion. From paisley patterns to kimonos and muslin, fashion and colonialism have a story that’s more intertwined than one might think at first glance. And yet, I do still adore fashion and clothes, and this is why I’m being so harsh on it, because I think it’s important to dissect and understand, so we can hopefully do better as we go.

On this, my darling listeners, thank you for listening to this episode of Imaginarium, I hope it was fun and we’ll meet again next month for a new episode and a new deep dive into another lesser known subject of art history and visual culture. If you want to support this podcast, you can do so on patreon @ patreon.com/nadjah. Otherwise, talk about it to anyone you’ll think will like it. And as the youtubers say, like and subscribe, and give us a good rating if you enjoyed. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you again very soon.