Plant explorers and botanical illustrations - the pitfalls of imperialism

IMAGINARIUM : An Alternate History of Art

Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

Hello dear listeners, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture. In today’s episode, we’re going to talk about botanical illustrations and the way the study of plants and its visual representations developed. Let’s discover the way it intersects with science, art and colonialism, I mean imperialism is just one of the usual suspects at this point, isn’t it ? This is a less artistic perspective of the visual arts, however it is still very much part of visual culture and our understanding of science through a visual medium, as well as helping the discipline of botany and the study of plant grow and advance. The landscape is as much a source of inspiration for art as it can be the template for art itself, gardens can be an outlet for creativity, and the shaping of natural elements has been often used in contemporary works of art and installation, i have spoken a bit more at length in episode nine of the first season on gardens in art. However today, as much as we will be talking a bit about the ethereal beauty of nature, our investigation of the topic will have a more scientific and pragmatic nature to it and will not have the grand emotions that accompany the philosophies and tenets of certain movements of art when thinking about nature. of the world of art. let’s delve into the world of botanical illustrations and scientific illustrations of nature and how these belong in a world of learning, botany, and sometimes, imperialism.

The symbiotic relationship between humans and nature is one that has had a constant push and pull through the years, I love love gardens and the feeling of being outside within the flowers, however I fully admit that I would simply never see myself as someone living in the middle of nowhere, I love the bustle of life around me and the options that urban life provides way too much to simply live in an isolated cottage, even though sometimes, it definitely feels like I would absolutely need to do that. Thank god you can rent a cabin for a getaway weekend every now and then ! I do think nature should have a much bigger part in our lives, if simply to not alienate ourselves from what makes us humans, and to not get a burnout when you spend your life constantly being busy and stuck in an environment thats polluted, grey and overwhelmingly visually ugly, like let’s be honest here, most of urban architecture from the past decades has been neither beautiful, neither particularly well built in the utilitarian sense as well, but that is only my opinion. I think, as a society, we deserve to have well designed useful and practical habitation, that are also visually pleasing. I just think we deserves beautiful and practical cities made for humans and not for cars.

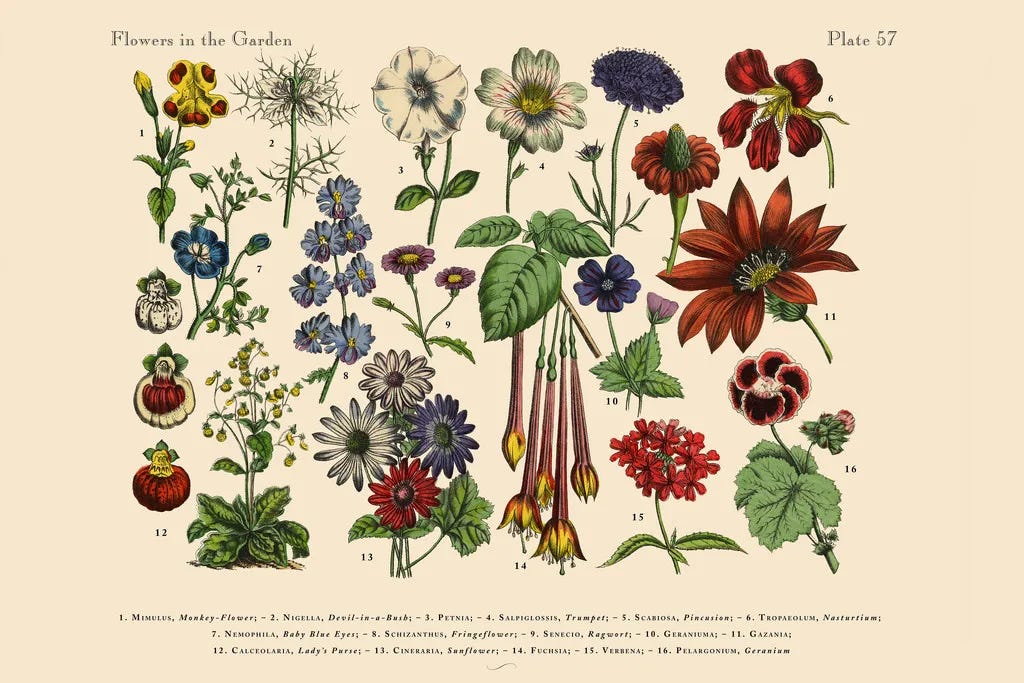

And so, this story that links people and human is thus one that has always been, and on an artistic level, nature has always been an incredible source of inspiration for artists and creative people of all sorts, and has been the basis of countless works of art and illustration as the main subject, because if there is one thing we do all have in common is the world out there, the sky, the sun and the nature that surrounds us, no matter how varied. It has always been out there, and we have always tried to capture its essence through art, but also to define and classify the way it exists. And so, the history of botanical illustration has to do with the fact there was a need to know and understand plants, especially way back in history when there was not the possibility to simply research things. People needed to know if the leaves that they were going to eat were edible or were poisonous, after all, a wrong choice could mean death, or at the very least a really terrible time. And so the knowledge of plant becomes absolutely vital on a medicinal and very practical way. Botanical illustrations, which are generally defined as being the illustrations that accompany or support a scientific text, tend to have a very practical purpose and are created with that specific goal in mind. The art, it is still art after all, is not one that is meant to be purely decorative nor beautiful, even though I do think they can be.

The history of the practice of botanical illustration can be traced all the way back to the ancient Egyptians and their numerous plant based hieroglyphs and this marks the earliest example of the way a herbal could end up being put together. On the walls of the temple of Thutmose III, you could fi nd at least 275 illustrations and hieroglyphs on its walls, which are detailed and complex enough that some of those plants are still recognizable today. In roughly 70-ish BCE with the illustrated book De Materia Medica by the greek botanist Pedanius Dioscorides, and genuinely, forgive my pronunciation on this one, however you know, an ancient greek botanist, and the purpose of it was indeed medicinal. He needed to be able to distinguish the plants that would help cure and solve various illnesses and ailments, as well as avoid the ones that were going to make matter worse. This particular work of ancient botanical science endured well into the modern age, and even in the 17th century was still used as a reference point. So, the correct identification of these plants was a matter of life and death actually, and thus was a very serious scientific discipline. Of course, as time went on, the purpose of the discipline broadened, and expanded. The use of botanical illustrations was thus as much as for the sake of the science in itself as it was for the purpose of creative skills of drawing and painting.

The medieval age in Europe brought a revitalization of the art of botanical illustration, with all of the manuscripts that were crafted in monasteries and it is then that the art of illumination and the beautiful miniatures that decorated those books. It was the age of sequestered monks spending their days away at their desks, painstakingly writing and drawing beautifully detailled books. And so, the herbals of the time, on top of being the testimony of an early form of science and a record of the nature around them, were also works of art. Those illuminated manuscripts were handwritten books, after all it was before the proliferation of the printing press, that were beautifully and meticulously crafted and embellished with gold or silver.

On top of that, the illustrations had to be copied and recopied, and with each further copy, straying even more from the original illustration as well, because the manuscript did not have the original plant as a visual reference, only the illustration, which makes the illustrations often inaccurate. Which, let’s be honest, is slightly unhelpful, and explains a lot the weird plants and a nimals that pepper western European medieval almanacs. This reminds me a bit of the 19th century orientalist paintings of faraway lands that were only based on travelogues, and thus were once and twice removed from the original landscape and country, creating thus only a an amalgam of reality, filling the blanks with some biased assumptions and ingrained prejudices. This is also how, I think, we got the weirdest drawings of exotic animals during the medieval era, people were hearing about elephants and lions and giraffes, as the monks were hearing vague secondhand descriptions of those faraway lands and animals and … trying their best I guess !

The nature of these herbals was very scientific, but also it is with this medieval understanding of science, which blends science and facts, as well as mysticism. For them, magic and alchemy were simply another facet of science, and this is why you would often see plants in these herbals that are known to be magical and have special properties, such as the mandrake root, which is a real plant, however the folklore around it is full of mysticism. This plant is depicted as having a human body and when pulled out from the ground, would scream and kill anyone who heard it. To the medieval people, there was no distinction between magic and science because it was one and the same, they were simply mirror images of the way the world worked, and so this separation between the two would have been meaningless to them.

And I can’t help myself to mention the voynich manuscript, dated to roughly the early 15th century , is a fine example of the way botanical sciences and species, even ones that we cannot seem to decrypt nor understand, are interwoven with the world of art. This particular manuscript, is one that is absolutely fascinating, as it is one of the historical mysteries that is still unsolved, because no matter how many people have tried to understand its meaning, no one has been able to pinpoint what the meaning or signification of it is. It looks like a typical medieval manuscript, and yet none of it makes sense. I do love that we still have some mysteries to try and decipher, especially when sometimes it feels like we have discovered and know everything, it is good to remember that we have not. The particular thing about the botanical illustrations of this manuscripts is that they represent plant species that seem to not exist in our material world, the plants and flowers drawn do not exist on earth, and have never been seen before. Of course, it could be simply be an invention or a prank, however, when you think about the price of paper in that era, this is a prank that was very costly to create. So this manuscript raises more questions than it answers, but the artistic style in which those botanical illustrations were drawn are very much in line with the style of the era.

When you look at the overall picture of this form of art, I think the history of botanical and natural illustrations can be separated in two distinct historical periods and artistic styles as well, before the advent of printing and after its inception. The year printing is invented is usually dated to1450, however it is mostly understood now that there are some printing technologies that predates it, the year of 1450 by Gutenberg is mostly a reference point for when printing became an important breakthrough in western culture, signa ling the beginning of a more accessible mode of communication. After all, books are way easier to produce and distribute when you do not have to manually write each and every one of them right ? And so, the 15th and 16th century really presents a shift when it comes to the way botanical illustrations are treated, after all, it is also the era of the renaissance, where the Florentine artistic scene is booming and going to influence so much of European art in the subsequent years. The stylistic changes during that era from the middle ages are getting a bit more stark, as it goes from more stylistic choices to a more realistic art style, that was more desirous to replicate and imitate the reality in front of them. Accuracy and realism became much more important, which was extremely helpful in terms of furthering the science and the correct identification of plants and flora.

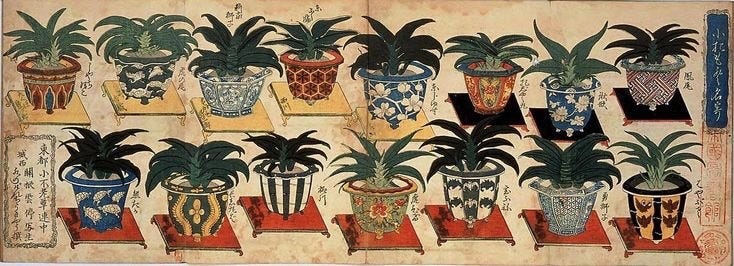

During the Islamic golden Age, from roughly the 8th to the 13th century, it was an age where the muslim scholars had a great thirst for knowledge of all kinds, and the science of botany, as a tool to support the development of natural sciences, but also for medicine and cuisine. The illustrations that were backing those scientific texts were not only a visual aid to teach and learn, the stylistic choices that were made during this era would continue to influence islamic art until today. The miniatures and illustrations are beautifully made and complex, and depict in details not only the plants, but also their many uses across the fields. The sciences in all their forms were a huge part of the medieval landscape of the islamic world, from mathematics, languages, astronomy, as well as the arts, from music, miniatures and architecture. Translating and transcribing scientific and philosophical documents from other languages and cultures into arabic was one of the ways to gain various knowledge from around the world, so there is a translation from de materia medica of dioscorides that we talked about earlier, from the 13th century in Iraq, written in arabic, with those beautiful watercolor illustrations that accompany the translated text. And so, there is a clear link between all of these botanical illustrations across not only space, but time.

What is usually called the golden age of exploration is those years following the discovery by the rest of the world of the American continent. People were traipsing around the world, bringing back seeds and plants sample to analyze and to grow, the field of botany and natural sciences was one that was thriving during those years. The people who cared about this subject were true enthusiasts that were ready to go out in the world, in unexplored and uncharted lands and bring back specimens of plants and flowers, as well as illustrate them. This is what made it so that the art of botanical illustration became such a fashionable one suddenly, where the goal was not only utilitarian, but also aesthetic. Botanical imperialism is a concept that must not be familiar to most, and yet it of course is one of the foundations of the way the discipline has grown in those years following the discovery of the American continent by europeans, during the 16th century and onwards. What I mean by that, is that it is that discovery that sent tons of what…well we can magnanimously call them explorers. Or maybe colonial leeches ? This is maybe too mean, but I do think we should be meaner to them, and anyway they’re all long dead by now.

Even if those people were not personally terrible people, the whole system of the imperial machine makes that perso nal motive totally redundant, because the imperialist system is what has been so harmful for so long, and so these quote unquote explorers, adventurers and botanists who were going around the world are simply part of the structure. There was a thirst for knowledge, however they were operating under an imperialist system within the Empire. And this where I want to get at. That it doesn’t really matter what their intentions were, the only reason they were able to go through to these exotic countries and faraway places, for them, was within a colonial project. There is no denying that science has been often used in support of imperialism and colonialism, after all, eugenics is the most racist form of sciences and we all know that it has no real basis in concrete reality and has been discredited time and time again. And yet, these theories were based on facts and figures that were interpreted through a racist lens. And so, this is what I mean by the fact that true objectivity does not exist, because even if facts and figures are unbiased, they will always be interpreted through our own biases and prejudices, and we all have them and have to work hard to unlearn the harmful ones. Eugenics were a significant part of the rise the fascism during the late 19th century and early 20th century, as science is often a tool to justify racism, colonialism, and spread the idea of a superior (white) race and the need to civilize and conquer certain countries and people, and so it was a rational and logical justification of imperialism, which is such a slippery slope.

This era is the one that defines and construct the figure of the courageous explorer and adventurer, an archetype that can be incredibly harmful, but is an archetype that continued to be extremely popular in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, at the height of the empire, and that continues to exist in current media, even if we are unaware of its ramifications. After all, it is a white savior trope as well as smoothing the figure of the colonizer. I mean, that is what Indiana Jones is inspired from, and while yes, it can still be enjoyed as just the silly action flick that it is, there is no denying that it is a slightly problematic archetype , after all, he goes to indigenous and non-western countries, which are depicted mostly as a monolith and backdrop for the adventure of the white explorer, never figuring front and center in their own stories. And so this figure of the scholar and the dashing explorer, becomes the lens through which the colonial project is often romanticized, it becomes an adventure, a dangerous journey at the end of which knowledge and treasure is accrued, no matter how those treasures and artefacts are stolen. And so, the idea that we have of exploration is unfortunate, because it is so often based on Empire. Even though, they were working to further science in the name of knowledge and all that good stuff, their true objective was to find plants and categorize them, however they also had a goal to find plants were going to be economically profitable to the empire, to then be able to exploit and make money out of.

The intersection between sciences, art and imperialism is where those botanical illustrations from those expeditions into the wild belong. There tends to be a desire to make art and sciences as opposites sides of a debate and put them at complete odds, as if there are no common ground between the two, however I do not believe this. I think both art and sciences are simply two sides of the same coin, if you’ll let me get away with the expression, however it is true, they are simply two different ways of understanding and making sense of the world, and there is art, emotions and inspiration in the method of science, and there is skill, logic and reason and discipline when it comes to creating art. And both of those areas wants to look at the world around us and try to make sense of what we have.

Hence, the world of botany and herbology is an important part of the way we understand the world around us, both through the lense of science and art. It is a vested interest for several people, it is a field that has several practical uses and where people needed to know the names and properties of certain plants, especially the ones with medicinal uses and useful properties, and a lot of people were experts in the domain, even if they were not necessarily professionals. A lot of these botanists and scientists, on top of having extensive scientific knowledge and ability, they had amazing artistic skills, because art and illustration was not a distinct discipline from their work in science, but actually was an integral part of their scientific research. Especially from the 18th century onwards, where the process of trying to document and classify plants developed in a much more technical way, but illustrations, despite its obvious shortcomings, after all, an illustration can only go so far when it comes to representing accurately the reality of the specimen that is being studied, however, with a skilled hand, there is a lot that the botanists could communicate and document about the specimens that they were encountering.

While women were often and heavily encouraged to help with plants and tend to their gardens and the growing their own vegetables and food, which was definitely a part of the way life and work were expected to be doing, women were a significant part of the quote unquote gardening community throughout the ages, there was very much still a door closed to them when it came to exercising in a professional manner, as a botanical scientist or as a landscape designer, or a professional working illustrator. Those fields of studies and options were still kind of closed to women until fairly recently and by this i mean the late 19th century. After all, doing it as a hobby and an amateur versus doing it within the confines of a qualified profession is very different in the eyes of society, no matter if the talent and skill is equivalent. This is like the example of the male chef vs the home-cook or the fashion designer and the seamstress, where the standards are very much unbalanced and biased.

.

Beatrix potter’s work in botanical illustration for one is one artist whom I have already talked about a bit in season 2 of this podcast, but mostly in terms of her work for children’s book illustration, and now we’re going to turn around and dive into the part of her body of work that engages with botanical illustrations and sciences. She was an avid enthusiast of drawing directly from nature, and that is how she learned and developed her craft, as well as got her inspiration for her children’s picture books. She had a genuine enthusiast specifically for the study of mushrooms. I know that strictly speaking, mushrooms are not plants, they are…. A third thing, scarier than anything we could try to come up with, insert here that absolutely terrifying tumblr post about how you cannot kill mushrooms in anyway that matters and how decay exists as an extant form of life. Look, mushrooms are just terrifying things, and that is my stance on that. However, Beatrix Potter did not share my opinion as she delved into the studies and meticulous illustrations of various mushroom species.

And yet, the fields of botany and plant studies were ones that so many people had a vested interest in, to the point of being experts in the subject, after all, there were practical and essential uses to this knowledge when people lead a life that is closer to nature, and so people needed to know the names and properties of certain plants, as well as be able to identify them. The intrinsic history of nature within human history, and the way this story was represented through art and visual culture. I am not a scientist, I am an art historian as well as an archivist, so it is through this lens that I’m approaching this subject, to see how what the art of botanical sciences says about history and our understanding of the world around us. The stylistic choices in botanical illustrations, often done in pencil or in watercolor, w a desire to transcribe to paper, as close to reality as possible, because the aesthetic was secondary to their practical purpose.

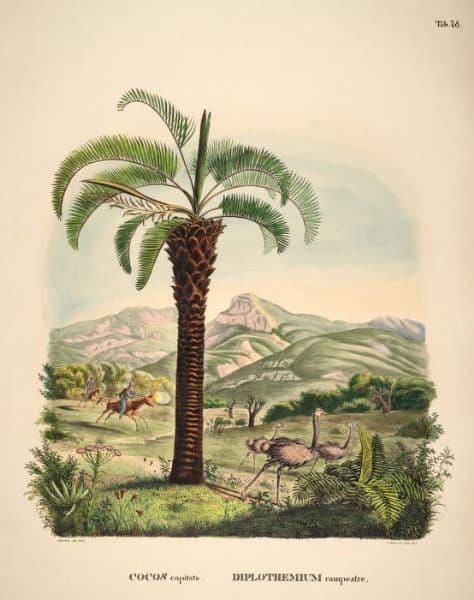

Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, who lived from 1794 until 1868, was a german botanist and artist, and is especially known for his palm illustrations. He went on an expedition to Brazil for king Maximilian I of Bavaria, and so, from 1817 to 1820, along with a zoologist, and their goal was to not only explore and research the natural history, but also the native tribes of the area, during their journey over two thousand kilometeres. He categorized and detailed a huge quantity of the palms and plants that are found in Brazil, an extensive work on which the modern delineation and classification of palms is still based upon. And so the work of Carl Von Martius is extremely important when it comes to botany and natural sciences, however, once again art and science are at the intersection of imperialism, during the age of empires, and while the headways of nature and science are important, there is still something a bit off about trying to investigate the indigenous people of the area in the same way, and taking advantage of them. However, the art that came out of these four years of expedition is a lush overview and a comprehensive analysis of the species of palms. His more than 240 illustrations are extremely detailed and instructive, on top of being extremely beautiful.

I hope that during the course of this podcast, I have underlined the way art and imperialism do work hand in hand, not only in simple and direct propaganda, but also the insidious ways it infiltrates the world of art and the depiction of various subjects and distorting them through the eye of Empire. The way culture, the global interconnected culture, is shaped, has the almost all encompassing influence of empire, the way we continue to understand the world, even in our modern era is still very much determined by these notions of empire, this is getting out of our subject of the Earth, but it is possible to notice in the vocabulary of how we talk about space exploration and space conquest, that the study of space is being understood within the lens of imperialism. It is a perception that has absolutely permeated the way we construct the world, and it is absolutely embedded within the system, and will unfortunately take a bit more than a few readings of post-colonial master theorists to untangle and resolve, but i do choose to believe and have hope that it can get better.

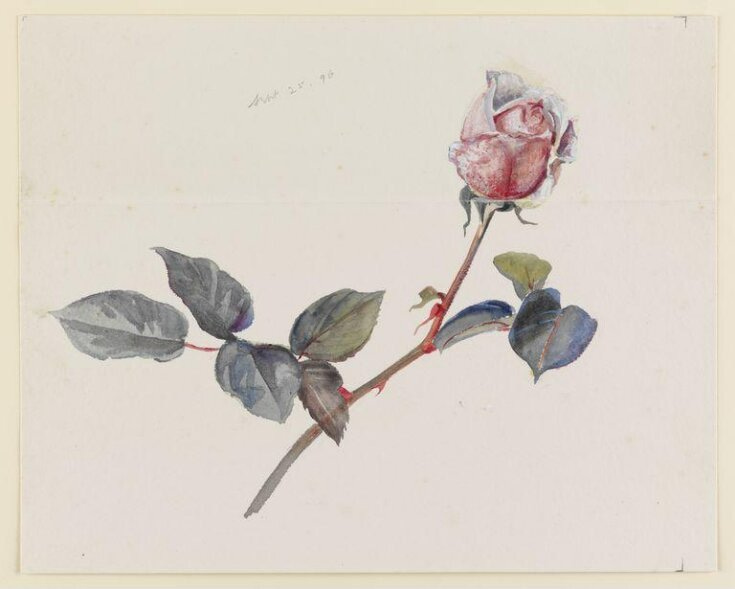

Pierre-Joseph Redouté was a french artist born in 1759 and who died in 1840, who exercised through the period of the late 18th century and to the early 19th century France, and whose illustrations of flowers and plants have in my opinion hugely influenced the idea of botanical illustration during those years. He was nicknamed the Raphael of flowers, not only, of course, because of his enormous artistic talent, but his extreme popularity within the fashionable world of Paris. He worked primarily in watercolor, to add of a sort of transparency and delicacy to his . Even if his work was mostly artistic and with a more decorative purpose, he was more of an artist than a scientist, however his illustration were a thing of beauty, and very precise in their realism and authenticity. Redouté, and his art, were part of an extremely tumultuous and intense historical period in France, from the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, all the way through the Terror and the reign of Napoleon. And it is a sign of the endurance of these illustrations, not only of their scientific significance, but of their aesthetic appeal, that they have been able to endur and travel through so many different eras and charged socio-political contexts, and still feel relevant and important. They represent a need that we feel to know more about our natural environment, but also to feel the beauty of our environment. A florilegia was created to also have a record of plants and flowers, but it did not need to have an extensive scientific description nor text accompanying the images, it was mostly just the illustrations, which were beautiful and often commissioned by universities and private estates. These objects that got into popularity during the 18th century, until the 19th century, where it was simply of good taste to draw some flowers, even though the purpose was not at all scientific, but the art of botanical illustration was increasingly in vogue.

Built in the 1759, the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew is an institution that is still to this day in operation, those gardens situated on the site of a former royal estate in London are some of the well known gardens in the world. With a goal of research and preservation, they were at the forefront of botanical sciences, and they had plant collectors whose job was to go across the world and collect plant specimens for the Kew gardens collection. During the 19th century, it broadened its activities to include a more instructional and recreational aspect to it by opening the Kew Gardens to the public, but also decided to further their work into the British colonial project. The history of the Botanical Gardens at kew is so entangled with the story of imperialism, it is impossible to separate the two and the way the knowledge and collection that are present in the Kew Gardens comes from imperialist expeditions, and it was a way to continue to profit from british colonies. However, and I will give that to them, the _ of he gardens, the y are aware and mindful of that history, and not trying to sweep it up under the rug and pretend it never happened actually, but fully cognizant of the brutal and violent consequences that colonialism can have, even if through something as lovely and benign as the study of plants and botany.To be honest, anything that has Royal in its title is simply part of the way the Empire has colonized and pillaged across the world, and I will say I do not pretend to know the best way to recover and from a history like that, but acknowledging it and trying to change the practices to be more inclusive and respectful is always a good start in my opinion and working toward correcting the egregious injustices that have been made back then, and so it is an institution that is at the cornerstone of botanical sciences, illustration and the way it was shaped through imperialism.

Of course, there is so much on this subject that I haven’t touched upon yet, the need to investigate and detail what surrounds us is universal, and this field is a broad one .Botanical illustrations exists as a physical representation not only of the pursuit not only of knowledge and science, but of beauty and artistry, the way those two can not only cohabit and coexist, but complement and inform each other. They are witnesses of our history in ways that are maybe unexpected, and yet, their presence, ubiquitous as it is, is a permanent reminder that beauty and violence are always intertwined.

On this, my darling listeners, thank you for listening to this episode of Imaginarium, I hope it was fun and we’ll meet again next month for a new episode and a new deep dive into another lesser known subject of art history and visual culture. If you want to support this podcast, you can do so on patreon @ patreon.com/nadjah. Otherwise, talk about it to anyone you’ll think will like it. And as the youtubers say, like and subscribe, and give us a good rating if you enjoyed. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you again very soon

.