Here is the last episode of the third season, all on fakes, art heists and forgeries, and the role of cultural institutions in this topic, i hope you enjoy 💞🩷

Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

Hello dear listeners, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture. In today’s episode, we’ll dive into the nebulous world of selling and buying fine arts, but most importantly, we will talk about the world of art heists, forgeries and art fakes. We’ll try and lift the curtain, if even just a tiny bit, on a world that is most mysterious to all those who are not in it. When we think of this mysterious world, there is not much we know for certain, from the outside looking in, something that is being done on purpose, to keep an air of mystique and exclusivity to that realm. Prices are attributed to objects or paintings, people with a lot of money show up and buy them at sums that are absolutely exorbitant by most people’s standards. After all, only a fraction of us can afford to buy a genuine painting of Van Gogh or a Matisse, and even if they could, there is a limited quantity of paintings that have been created, which adds to the exclusivity, and the sentiment of scarcity. Auction houses can sell many a things, from art to furniture, to jewelry and cutlery, and these can be available to everyone who might want to purchase something, and yet even though they are public, they still feel off-limits to the masses, as if the intricacies of it are closed off to the rest of us, mere mortals. And while, anyone can go to an estate sale, or purchase a nice desk at a regional auction, there are certain auction houses that specialize in selling only the rarest and most expensive of items, auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christies, which are known globally for their extremely rare objects and art.

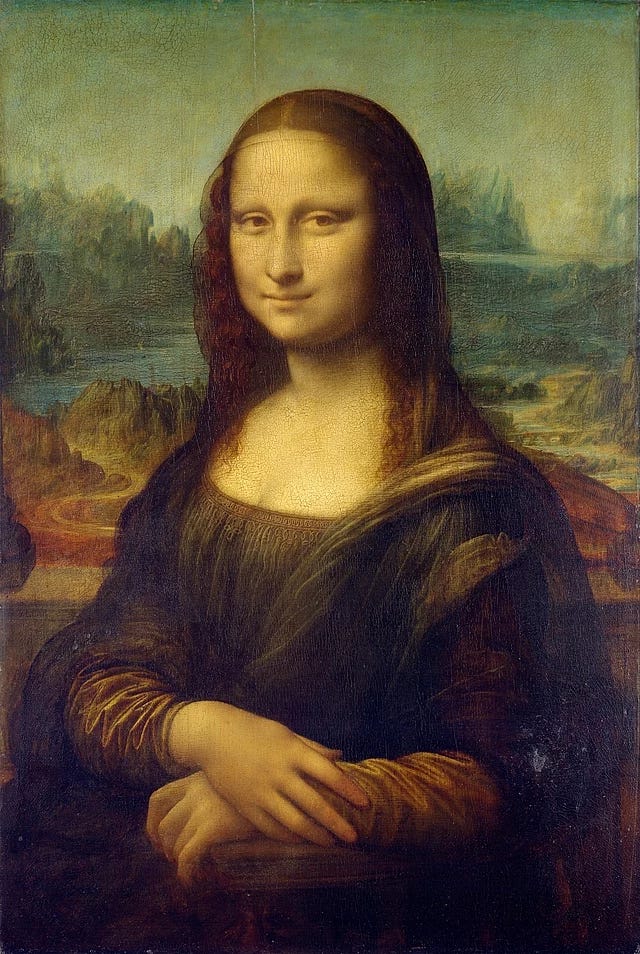

The way the world of selling art works, well, at least, the world of fine art, is one that relies on status, exclusivity and exclusion. While other fields and disciplines of art such as illustration, for example, relies on prints and copies, ensuing an accessible and reliable supply of material, you can print a work of art again and again, and sell it to as many people as you might want to, and that is the goal of it, to be copied and seen times and times again. Meanwhile, when it comes to fine art, it relies on there being one unique example of the piece of art. The value of the Mona Lisa simply would not be the same if there were infinite copies of it all made from the hand of Leonardo Da Vinci, it is the fact that it is considered to be one of the most precious and most well known works of art, and it is the only one. It is the only one that had been specifically made by that artist’s hand, and that was created using those materials and paints only available during the early 16th century. And so, for that reason, and myriads of others that can be discerned, and some which are more obscure, it got established in the cultural consciousness as an extremely precious work of art.

When it comes to status and society, art has always played an incredibly role in the way the elites have shown their wealth and position in society. And this is arguably a very simplistic way of looking at it, social spheres and dynamics are incredibly complex and subtle in a lot of ways. In ages past, the social hierarchy was as complex, however, knowing where one belonged on the ladder was easier than it is now. I think that works of art should be appreciated on their own, without any thought to their monetary or social value. I think you should be able to look at a painting, at a piece of art and appreciate it as it is and how it can connect with you. Sometimes it will be a painting, sometimes it will be a sketch or a specific embroidery, a sculpture or a performance, art exists in so many forms, and it is to restrict the definition of art to confine it only to the classical forms of art. However it would be naive to believe that this is the only way people relate to art, and there is no denying their function as a status symbol. A function of showing where one belongs in the social hierarchy. When it comes to status, as W. David Marx says it in his excellent book Status and Culture, status is something that is bestowed upon another one, so for someone to benefit socially from owning or commissioning an expensive piece of art, it must be generally known how much the work of art is worth and who is the owner. And so, the more exclusive things are, the more status they give.

Patronage used to be a mean that the rich and famous would take as a way to assert culture and taste. And, even though, it is sometimes about the art, it was about the fact that they showed off that they could afford to patron and finance an artist. And so art became a status symbol, which it is, when the art costs several millions of dollars to buy, there is no way it is only about the art, but about what it says about the owner’s place in society, about their power and their wealth and their good taste. When you think about it, expensive works of art have always been an efficient shorthand for a powerful show of status, from the extremely expensive portraits and ornaments that people were commissioning of themselves in full costumed regalia in the western aristocracy at a time where the simple act of being able to dress in such expensive and refined clothing was reserved to the ultra rich to the white and chrome penthouses in which is hung one gigantic painting in the center of the wall, a single painting that you immediately know costs more than what you would be able to save in your entire life. In those paintings, both the content and the context of the object in itself can be a sign of status.

The work of art, and by that, I mean the content of the piece, can be a very ostentatious display of wealth, whether it shows a king decked in his most expensive outfit surrounded with pieces of art, a few hounds and scientific objects, with their gigantic castle painted in the background, or the object in itself, the painting, this was a detailed depiction of how rich and powerful the person was. These subtleties and intricacies of visual literacy might have gotten lost in translation in some ways because it is always important to remember that the past is in effect, simply a foreign country, as the title of the book by David Lowenthal explains it. And I know I might have already mentioned this book before, so please forgive me the repetition if you have heard about this book before, however, it is really helpful to consider when trying to discern the visual representations of social status in the past. Understanding their symbols of status would be akin to understanding a completely foreign culture, with its own language, societal norms and ideas. The same way when we see a specific style of clothing or a certain brand of watch or shoes, and we know instantly that this signifies wealth and a certain rank in life. Even though, I have to admit that these ideas and the way wealth and status are understood in the 2020s are constantly shifting and changing, and especially with the appearance of wealth and status being more accessible to people, for example when you see people renting private jets in order to post a picture on social media without ever having flown these planes. All this to say that the symbols of status that we find in works of art of yesteryear might not always be intuitive to us, but contemporaries who would have seen it would have understood what that meant, and what that show of power would have communicated to other people.

Visual literacy is about looking at something, and not only a work of art, even though that is definitely part of it, but it can be a painting, but also a graphic novel, an advertisement, the design of a website, it’s about the way something looks, and what that conveys to you. It’s about being able to understand what an advertisement is trying to communicate to you, and thus being less susceptible to be swayed by that same advertisement. It’s about looking at a page of a comic without any text and understanding the emotional narrative of that image. In a digital world where images are being constantly shown and bombarded to us, being able to understand them, and being able to read those images is absolutely paramount.

The monetary value of art is something that is very difficult to ascertain, because on one hand, there is the affirmation that art is priceless, but also putting a price tag on the value of art is a weird process to be sure. And so the peculiar and nebulous rules of the elite world of fine arts, which are ever changing and kept well under wrap to outsiders, definitely are created with an exclusionary view in mind. First of all, what distinguishes Art from more commercial artistic and creative ventures such as design, whether in terms of designing a house, a garment or a poster, or craftsmanship such as embroidery, ceramics. After all, all of them are creative endeavors with equal merits. Why are some works of art priced the way you would price an employee ; for example if you get a simple commission from an illustrator, usually priced at a flat rate that considers how much time and effort has been put into the piece. And meanwhile some pieces created in the same vein are priced in the millions and millions of dollars. The process of evaluating and assigning a number to these works of art is called appraising, which considers different factors such as the rarity, scarcity, the general canon of art of that artist and its place within the grand timeline of art history. Popularity and the social capital the artist or that particular piece of art have is also an important criteria, and so they consider all of these elements and more to put a value to a piece of art. However, these type of appraisals are very finicky and subject to change very quickly, I mean how often can an artist get embroiled into a scandal or say something that will diminish their social capital and suddenly no one wants to buy a piece from them.

First of all, I think it is pertinent to explore the idea of what is art. I mean, I do feel like this is a maybe a tall order for our short podcast episodes, but it still might be pertinent to think about it a bit before we get into the the art fakes. what makes the original ones art ? And are forgeries able to be considered as real art ? After all, it takes a good amount of technical talent to reproduce certain pieces of fine art in a way that is imperceptible to the naked eye. And yet, one of them is a genuine piece of art, and the other is merely a simple copy of it, and so copies, are an incredible important part of the world of art, and even more so in an age of mechanical and digital reproduction, as per our good friend Walter Benjamin and his essay : The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. And so let’s dig a bit into the philosophy of copies.

In ancient art, the original artist of a work of art was not as important as it now is, throughout the years, the cult of the artist became a sub-category of the cult of celebrity, and we assume that this is just how things have always been, however it is not the case. During the antiquity, for example, the people who were making the statues were not the ones that were remembered and valued, and their work was not singular. Statues were made to be copied and copied again, and this process did not diminish the inherent value of the art. So i think it’s safe to say that we can distinguish at least two distinct types of copies. Ones that are made with the deliberate intention of being passed as the original work of art, and the copy that is simply a replica of something else. For example, I have a small frame of a Monet painting in my room that i found in a thrift shop, but I have no illusion about it being the real one. I think this can definitely be compared to the way, maybe, our understanding of art functions now with our digital world, the reproduction of art and its endless copies due to printing, but mainly to the internet and our tools of mass communications. Does it affect the monetary worth of a painting when you can view a high quality image of that same painting whenever you wish to ? Our understanding in itself of what is art has changed throughout the ages, expanding and constricting as the perception of what a work of art can be has evolved with the culture.

Therefore, the cult of the artist is something that is fairly new in the art history timeline, they used to be perceived as craftsman. There were of course certain figures of art that were hugely influential, but artists were hired and had the patronage of rich and powerful people who had either an interest in art, or an interest in looking like they had an interest in art. Successful artists had a whole crew of assistants and helpers, so truly how much the art was created by that one person, and how do you really pinpoint one person as being the sole artist in these circumstances if it is a collaborative effort. It’s the same way with movies, people credit the movie as being the sole creation and oeuvre of the director, but it is the ultimate collaborative creative effort with everyone bringing their efforts and skills into it, no movie can be done by a single person, the director, the writer, sure, but also the costume makers, the director of photography , and it is also these tensions between every players that makes that work what it is.

It is the Renaissance, with Vasari’s lives of the artist, which is often considered the beginning of what we now know as art history, and most importantly of the way we think about the artists. This book is a very … well you have to understand that art history and history in general being thought of as an objective kind of discipline where the facts and the dates are very important is very recent. For a long time, history was more or less used more as a tool of propaganda or myth making, and really should be taken with a grain of salt when it comes to their historical accuracy the further you go back. They would weave actual facts with legends and rumors, and sometimes just straight up lie because why not, it was more about telling a good story rather than record the true facts on paper. And so, to go back to Vasari and his lives of the artists, it was one of the first time the focus was on the artists and their works. There are so many things that we consider as immutable and fixed in stone, and they are not. Our understanding of art and art history is definitely particular to our specific moment in history, when you explore another era or another country, this understanding of what is art and what is a copy will also shift because the culture in itself will be different. The way art and copies were understood centuries ago was not the same as now, there was not the same inherent value in the original work of art. It is sometimes easy to forget how things that seem so inherently obvious to us, are only a social construct. they are this way because we have decided them, as a society, collectively, for them to be this way, over years and decades and centuries.

When it comes to roman and greek statues, they are an example of how copies can be an intrinsic part of the artistic process, to the point where 18th century art historians thought the roman statues were greek because they were extremely similar copies of ancient greek statues. It was a conclusion they reached with the information they had during that era, which is why it is always good to remember how fickle our knowledge of anything truly is really, and we are always drawing our conclusions from the knowledge that we currently have. Maybe a new information will be dug up from the earth tomorrow that will shatter our entire knowledge of how the world functions, but until then, we do what we can with the information that we have. And hope future generations will hopefully laugh at us kindly when they wonder how we could have ever though that this fact or the other was true or not. And so, the history of art and art copies, is simply a history of the way art was understood and valued during a specific point in history.

What is the purpose of a forgery versus the purpose of a copy. You might say the two are one and the same, but not necessarily. Some artists will make copies and studies of works of masters of art, and this is a normal part of the process of learning how to become an artist. As long as you don’t present that work of art as being your own, there is nothing wrong, in my opinion, in doing this, because emulating artists that you admire, and see what parts of their art and their styles you want to make your own is truly simply a part of how you can learn to become a better artist, both on a technical and artistic level. However that copy will still be a copy.

There is also general trends to consider, where artists created works in the style of a popular artist of the time as a way to make money, and while in a sense, it was not a real copy, after all, they were not pretending to be Raphael or any other successful artist, they are simply copying maybe a general style. And on the one hand, it let people have a sense of that sort of luxury that they couldn’t afford without paying for the real thing, and on the other hand, sometimes artists appreciated this kind of homage, because it cemented their personal style in the cultural zeitgeist of the time, but also within the historical narrative. It is a system of trends and styles, and so the inherent purpose of a copy is not necessarily a negative one. Even if a copy seems an exact replica of another work of art, even on a formal and material level, they will not be the same. Indeed, even the best copy of a renaissance master will have the impossibility to recreate the exact same pigments and canvas, because this one painting will have been created in the 16th century and that one in the 21st century. And thus, no matter how exacting the copy will be, it will still be only a copy and a recreation, and will not have the same historical value.

There is a show that I have watched a couple of seasons from which is the BBC show Fake or Fortune, where they investigate if the work of art of the episode is a forgery or is the real deal. Art dealer and art historian Philip Mould and investigative journalist Fiona Bruce are teaming up to try to assess if a work of art is the real deal or if it is a forgery. It is a fascinating show where they delve deep into not only the history of the artist, the artwork and the context in which it might have painted, but they also try to trace back the provenance of the painting. The provenance is one of the most important element to be able to confirm or infirm the authenticity and value of an artifact, especially the older it gets. We need to be able to retrace the history of the painting, ideally, back to the original owner or to the artist. The provenance is not only needed, but primordial when it comes to attesting the legitimacy of a work of art. To prove, for example as in one of the first episodes of Fake or Fortune, that this painting is very much a real Monet despite that it is not present in the Catalogue Raisonné. The catalogue raisonné is a complete inventory of all the artworks of an individual artist, and so any work of art that would not be in the catalogue would then be deemed a fake. However the team of investigators from the show has managed to retrace pretty strongly the history of that painting in a convincing enough way that you could definitely argue for it to be a real Monet. And yet, if the experts who are handling the catalogue raisonné do not agree with that conclusion, it can never be sold as a real Monet, and thus will never get the astronomical sums to which the paintings of that artist are often sold. And so, this is a very interesting show to watch, as a lover of art history, but also there is something to be said about how value and authenticity is assigned, despite the fact that this painting might be a real one, if it is not admitted by the experts and leading authorities as one, then it cannot be considered as one, and will only ever have the value of a copy.

However, a forgery, unlike a copy, is created with the formal intent to deceive. to fool and to extort money from people who believe they have just paid for the genuine thing. Which is different from a simple copy that has the intent to pay respect or simply to study a particular artist or movement. Truly, the intent to deceive as the object being a real one is a key part of what a forgery is. Of course, that is a crime, and I want to say that I do not support thievery and crime and I will never condone it in any situation whatsoever and this is the official Imaginarium podcast tagline, HOWEVER, I have to say that the topic of forgeries and art theft is one that is kind of extremely fun, because even though it is a crime and can definitely hurt people, even if not in the same way violent crimes would. But I just have to say that there is something about a good art heist that is always so satisfying to me, whether it is a real heist or a fictional one. I hugely recommend the movies How To Steal A Million in 1966 starring Audrey Hepburn and Peter O’Toole, as well as Topkapi in 1964 if you want to have a good dose of highly fashionable and highly fun heist movies from the 1960s. They are genuinely so enjoyable and immensely stylized and I adore all of them.

One of the art heists that is still captivating the imaginary of most, or at least, I guess i should say mine, is the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist of 1990, one of the largest art heists of all times, and how none the artworks has still not been found more than 30 years later. Two men dressed as policemen entered the museum in the middle of the night, tied the security guards in the basement and after almost an hour in a half into the museum, they left with thirteen works of art, never to be seen again. Works of art by extremely well known artists such as Rembrandt, Vermeer and Manet, pieces that were already judged to be extremely valuable, but now will probably be even more so, if they are ever recovered. One of the most compelling things to me, when it comes to this museum, is that the empty frames have been left up in the museum, as a tribute to those lost paintings.

A heist can add value to a painting, after it truly is only after the Mona Lisa got stolen in 1911 , by Vincenzo Peruggia, he claimed he wanted to give the painting back to Italy, the reason he took the Mona Lisa, and not any other paintings, was not because of its value, artistic, historic or monetary, but because the Mona Lisa, as anyone who ever visits the Louvres can tell you, is a surprisingly small painting, and so was easily carried away. And it is that notorious theft that made it so this particular work of art got cemented in the cultural zeitgeist as a canonical work of art and stayed there. The Mona Lisa was a well known painting before that, Leonardo Da Vinci would always be one of the masters of the renaissance after all, but it was this association with this crime and the high profile coverage of the case that made the Mona Lisa what she is today. However talking about copies and fakes, there are some theories that affirm that the current Mona Lisa is a fake, that during those two years where La Gioconda was out of the hands of the museum institution, someone made a really good copy and kept the real one.

And so, this story is one that adds to the cultural fascination with the Mona Lisa, this painting is one of those extremely highly priced oeuvre, being approximately valued to an entire 860 Million dollars. After all, even the person who is the most uninterested about art could visually identify it and tell you that it was painted by Leonardo Da Vinci, it is one of those paintings that is simply part of culture in a way few other art pieces are, if any. After all, it’s a work of art that’s been parodied to the extreme and that has also been analyzed and interpreted. I usually prefer to talk about lesser known works of art history on this podcast, because truly what can I tell you about the Mona Lisa that hasn’t been told ad nauseam by everyone else after all, it is one of the most debated works of art out there. However when it comes to understanding the world of art, the canon of art, and why these works of art can be so crucial to the understanding of culture, status and society, I think we cannot ignore the Mona Lisa.

Are art forgers also artists, after all, good forgers are extremely skilled and knowledgeable in art but also art history, their technical dexterity makes it so that the copy and the original are undistinguishable from the other. And, so do copies also have value, both in the artistic sense and the monetary sense, or are they meaningless fabrication, in a world of extreme mass communication where I can look at an extremely good quality image of a work of art, what is the importance of the authentic art ? Even if, at first glance, a work of art and its forgery look the same, after all they are not. But, how do we value the work of art and its copy, is that value truly intrinsic, or is it a value given by our social and artistic capital that has been built over the years. However, a copy will only ever be that, you cannot replicate personal and human creativity, there is something about the artistic impulse and personal touch that cannot be replicated.

Stories of heists and dramatic art robberies can feel compelling, there is something about those crimes that feel democratizing, in the sense that art should belong to the people, and that stealing those extremely valuable works of art feels like stealing from the rich. And sometimes, it is stealing from the rich. However, when it comes to stealing from museums and cultural public institutions, who you are really stealing from is the public, and we will get to the museum as an institution later on during this episode, however, no matter its numerous issues, and they exist, they are a way in which art and culture are accessible to the general public, and not only to an elite circle of few people. And yet, there is something about a museum heist that is so compelling, I mean i know i am still absolutely fascinated by stories of heists, there is something about these stories that is incredibly ocean eleven’s esque, it feels almost fictional.

But these stories are often stranger than fiction, after all, there is only to discover a little bit about Arthur Brand and Octave Durham to fall into a rabbit hole of stories about thefts, secrets and schemes, that feel so entirely out of this world, and yet. Arthur Brand is a private art detective, specialized in retrieving stolen works of art, and his working partnership with Octave Durham, a former professional thief, with two stolen Van Goghs in his arsenal, and they are now working to prevent art thefts from happening, as well as recovering stolen artworks and getting them back to their legitimate owners. The cases in which they have been embroiled are so extraordinary it defies credibility, and yet these are things that happen out there in the real world. First of all, I just want to say that the title of art detective is so extremely cool and I am absolutely in love with the concept of people being specialized in getting back stolen art to museum institutions, and even to their original countries as well. Arthur Brand advances that up to ten percent of art pieces in museums are actually fake artworks, which is an absolutely insane number of art pieces that this concerns, and this is only the pieces that are in actual institutions, and not considering the pieces in art galleries or bought by individuals who might not want to admit that they have purchased a fake to the cost of enormous sums of money.

When it comes to art thievery, however, we do have to give a slow clap to the most talented art thieves in the whole entire world, because not only they are the ones to have stolen the most art and artifacts in history, but also, and that is the kicker: they did it legally. And this a story of the best art thieves in the world: the British Empire. And so, I’m talking of course about the British Museum, which houses the largest amount of stolen and looted goods in the whole entire world. To be fair to them, they are not the only one, all colonial powers are thieves, but the dynamic duo of France and the United Kingdom's are the chief colonizers, but they truly are not the only ones, just quickly I can also mention Belgium, Italy, Japan, the United-States of America. There are a lot of countries that were part of the imperialist machine, a lot of European countries wanted in in the idea of having colonies over the world. The globe became a giant chessboard of who could get the most territories and profit out of them, and colonized people were simply collateral damage to this territorial expansion.

There is an important conversation that’s being currently had about the looting and stealing of priceless art and artifacts from colonies and how these items should be given back to their original countries, however the British Museum and company are probably doing the equivalent of putting their fingers in their ears and pretending they can’t hear you nor see you. But justice needs to be served, and these items should be given back, especially after they had been stolen in such terrible circumstances. And sometimes, well sometimes people take matters into their own hands. In 2009, there was an auction held by Christie’s in which two bronze sculptures that were looted from China in 1860 during the Second Opium War were being put for bidding. Those two statues, the head of a rat and the head of a rabbit, were part of a sale of artefacts owned by Yves Saint-Laurent, the french designer, and so, they were sold to the highest bidder, Cai Mingchao for the enormous sum of 28 million euros, a sum that he refused to pay, saying that these objects were not Christie’s to sell, as they were the property of China, as they were looted and stolen goods. They did end up being donated back to China, however this raises so many issues when it comes to historical artefacts and their provenance.

In the spring of 2023, Investigators seize $69M worth of stolen artifacts bought by Met trustee Shelby White, which. Let’s be honest, just as a headline and as a sentence is enough to be absolutely bonkers. Of course, this is still an ongoing investigation as far as I know, and so very much allegedly and news have said that . Etc etc etc. However, the fact that she had this many looted artifacts in her home, 69 millions worth (nice) means either one of two things, as she was on the committee of acquisitions at the MET, either she does not know what she is talking about when it comes to acquiring artifacts and making sure you do not acquire looted or stolen pieces, which would be extremely damaging to the Metropolitan museum, as it means that they do have people sitting on their committes of acquisition that are not qualified for that position and are only there because they would have made sizable donations and have gained influence through those channels. And if she does not know what she is talking about, how many pieces did the MET acquire that are possibly looted or stolen artifacts ? This is if she was indeed not aware of having bought, I repeat it once again, 69 Millions dollars of looted art (nice), which is in my opinion, very unlikely. The other option is that she was aware and bought them purposefully without caring that they were looted, and this would be a testimony of the lack of care about the iffy and often cruel provenance of these artefacts, and would look the other way and not do her due diligence to assess the origin of these pieces only to be able to possess those works of art. As it stands, she says that the artifacts were bought by her husband while he was alive. I guess dead men truly can’t talk. Or defend themselves. No matter if she is guilty or innocent, the situation is not good for the MET either, because either they have put on their comittee an incompetent or a criminal.

Fakes and forgeries have an intimate relationship with the colonial enterprise, the trafficking of relics and historical artifacts, as well as the counterfeiting of copies from colonial regions, was especially a problem in the 19th century, when imperialism and tourism in the colonies was at its peak. Personally, I think the colonizer kinda had it coming, but what do I know. Counterfeit ancient Egyptian bowls were sold to unsuspecting visitors who wanted to bring back home a taste of quote unquote authentic history. So often, the driving force of these copies and forgeries, is very simple. It is only about money in the end. It is about simple profit, art is extremely profitable and people simply want to cash into that without having to make the effort of sourcing the actual artefacts. However, this sort of fraudulent business, as much as it, you know, very much is a crime, is nowhere as impactful as the consequences of imperialist looting during the colonial project.

The 19th century was a century of looting and stealing in non-western countries by a lot of western institutions, this is true of most imperialist powers, but I think even more so of the everlasting dynamic duo of imperialism : the french and the english, whom, in the early modern era century, had territories all across the globe, from the americas, Africa, the middle east, Asia, and honestly at this point I have named the entire world. There is a joke that goes like this : the only reason the pyramids of Egypt are still where they were built is because the english did not find a way to move them back home. It is funny jape, but I do think that it does have a ring of truth to it considering that actual ceilings and walls and tiles that were moved to the museums of the imperialist homelands, such as the zodiac ceiling of the Temple of Denderah. it is a ceiling more than two thousand years old that show cases the exact night sky that people would have seen during that time. It was taken off from its rightful place with gunpowder and explosions during the 19th century, simply because the French decided that they wanted to take it, and everything that was coming from a non-western country was fair game. They decided that France must have it, and it is this very entitled and colonialist attitude that still governs a lot of the way art history and museum curating has evolved. And so, there is no way to separate the museum from its role in the imperial machine.

The art world and the art canon, are, by design, tools of imperialism. I know this might seem far-fetched, however please stick with me while I try to explain. I know that a lot of people doing art history and being part of the broader spectrum of the art world are against imperialism, after all, there has been so much progress and pushback within the field with the rise of post-colonial theory and decolonizing actions that are being taken in cultural institutions now. But you have to understand the way the art canon, in a general manner, functions, and the way art history, as a discipline, got established has to do with pushing a specific idea of art and culture that conforms to the ideals of white supremacy. Most of the art works that are in the art canon, and by the art canon, I’m not saying there is an official list out there that’s like « here are the works of art that we consider as being part of the art canon » being ratified by an official council of Arts or whatever. However, there is a general idea that’s pretty established in the general culture of what are the works of art that everyone should know, a list that has grown organically through time and was reinforced by academia and culture.

Is it even possible to truly decolonize an institution and a world whose every tenet has been constructed from an idea of colonialism and empire, after all, the entire institution from the ground up was built on an imperialist world view. The concept in itself of art, and the art world, can be a tool of imperialism. It has often been, and continues to be used as such, from propaganda to keeping the artifacts that do not belong to them. Saying you are decolonizing is very well and good, but words are just that, and unless actual acts follow… well it is as good as the wind, and it doesn’t mean much in the end. I don't know how we would go on to reform this system, because the way I see it, it needs to be entirely destroyed and built anew, because the basis itself of the system of art is based on imperialism and capitalism. The idea of a global art canon is often western centric and reductive, and does not consider the true reality of a world of art history. Even when people make a global world of art history, the emphasis is often put on western works of art with maybe a token pieces from non-western art as to make it seem complete, however, this construction of the world of art, is one that is built upon with an idea of white supremacy underlying the construction it itself of that canon. The concept of authenticity, copies and value is a fraught one in art, and one that is constantly shifting as culture and the march of history progresses on, but what is certain is that with the current debates on artificial intelligence and the way it is used to steal from artists, this debate will be one that will continue to be extremely important in the culture.

On this, my darling listeners, thank you for listening to this episode of Imaginarium, I hope it was fun and we’ll meet again at some point, for a new episode and a new deep dive into another lesser known subject of art history and visual culture. As this is the last episode of this season, I will be taking a short break from the podcast until the next season is written. Until then, I will also be on substack, which like hi I have started a substack, and the link will be in the shownotes, I do hope you support it and follow along, I will definitely try to publish as often as I can within my schedule. Otherwise, talk about it to anyone you’ll think will like it. And as the youtubers say, like and subscribe, and give us a good rating if you enjoyed. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you again very soon