Welcome to Imaginarium: an alternate history of art. A podcast where we delve in to the most obscure parts of art history.

Hello, I’m your host Nadjah, and in this podcast, we try to shed light on less studied parts of the history of art and visual culture.In today’s episode, I'm going to talk about one of my favorite algerian pictural artists, as well as the context in which she lived and practiced her art, aka colonized Algeria and then through to the independence of the country. Hopefully, this will be an episode that will join both lesser and hidden parts of art history, but will also shed a light on colonized history and how it’s truly not as far as some people think it is.

Let’s begin.

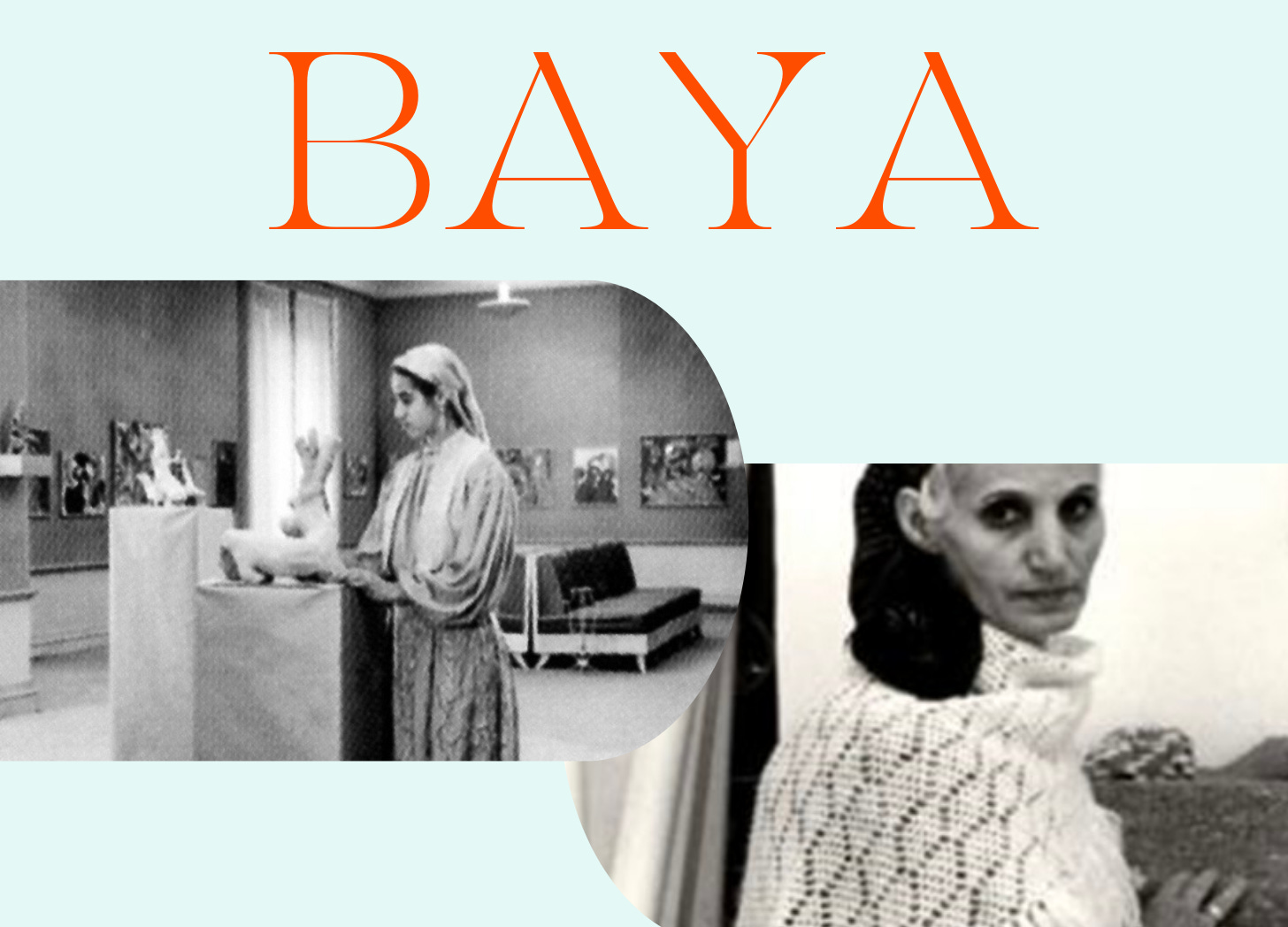

Baya mahieddine : flowers under the jasmin. notes of music through the bombs.

Bright and contrasting colors, delicate swirls and bold lines, the work of Baya Mahieddine is well known in certain artistic circles, especially those that are interested in the history of algerian art, surrealism and modern art.

Nonetheless, it’s still a name that’s often unknown to the general public or to someone who only has a passing knowledge of art history. Which is, in my opinion, a shame that such a talented artist, and who had such a unique vision, had mostly been relegated to obscurity, while her western counterparts, that were active at the same time as she was, often have entire courses being dedicated on their art and lives. Books upon books have been written on Picasso, or Marcel Duchamp. Names such as Piet Mondrian, René Magritte are being remembered by history and their works are still very easily recognizable by the average person.

Baya Mahieddine, who simply went by the name Baya, and whose birth name was Fatima Haddad, was an algerian pictorial artist who drew masterpieces that were considered to be on the same level as Matisse and Picasso while she was at the very young age of 16 years old. Her paintings had a very distinct and recognizable style, it’s very easy to single out a piece she created. Yet, neither her art, nor her story are remembered by history (or at least, white western history) and the field of art history on the same level as these men.

This is a story of a woman, of a country, colonisation and, hopefully, of justice.

Bordj-El-Kiffan (way before) :

Born in 1931, in Bordj-El-Kiffan on the outskirts of Algiers, Baya Mahieddine lived in an Algeria who had just recently passed the hundredth anniversary of the french colonisation. Life in Algeria during that time was not easy for the native algerians, the french people built villas and summer houses and came to enjoy the sun, the warmth as well as the exoticness of the quote unquote orient. The algerian colonies were there for french consumption, of its resources, of the imperialist violence that had become now mundane after so much time.

After the death of her parents, the young Baya Ended up being taken in by the french family who used to employ her grandmother as a maid.The details are a bit murky here, and every source i seem to find do contradict themselves when it comes to the specific details, of whether she was only been taken in as a servant or if she ended up being actually adopted. What everyone seems to agree on, is that Baya lived her younger years with this french family.

This was Algeria of the 1940s, where independence was only still a vague dream that seemed more like smoke and shadows rather than reality.

Algeria has been colonized by France from 1830 to 1962, which is a full132 years of colonization, oppression and injustice. My own grandparents were both in their thirties when the independence happened, I just want to stress how recent this all was, and how much violence was put upon the algerian people in a show of power by the colonizing powers of France. I always find it very ironic how France is heralded for being the example of democracy and freedom for the people after taking down their monarchy in 1789, but this goes to show that this sort of thing is only valid when it comes to white people. The french, and tbh, white people in general, had proven time and time again that their vision of democracy, of who deserves to have the dignity of being a person never truly included non-white people.

And this is how we can have the dichotomy of being known as a country who has made great steps forward in democracy, freedom, justice, and yet still being an imperialist power who has colonized many countries, if you look up which countries France had colonized, it includes all of north africa, west african countries, territories in India, China, Sri Lanka, Syria, Lebanon, Guadeloupe, and so forth and so on. I think it’s important to talk about how this double standard existed back then, and still very much exists today. This is why the lives of non-white people weren’t deemed as important. This is why the art and creativity of non-white people wasn’t deemed as valuable, apart to steal from them.

The incident that started the colonization of Algeria is known as the Fly Whisk Incident which happened in the spring of 1827. Entire books could be and have been written on the subject of algerian colonization, but to simplify things, what happened is that France refused to settle an old debt they owed to the city of Algiers and the Dey of Algiers got understandably annoyed and dismissed them away with his fly whisk, tired of the excuses they kept giving for why they couldn’t pay back their debts. Which is what kickstarted the colonization of algeria (because some people are fragile and cannot take no for an answer, especially from people they considered lesser than they were)

The city of Algiers used to be a power in its own right, dominating the coast and was very strategically well placed in the mediterranean. The white walls of the city were a well guarded fortress against the western powers that be. and it was a muslim and “eastern” city. And the white western pride of France was hurt so they retaliated. There’s more to be told of course, of the historical events that happened during that period, but this is how Algiers finally got taken as a french territory. France’s fortune was built on the back of its colonies, stealing the resources from the algerian territory.

The algerian war and the independence were obtained with a lot of fight, violence and blood, because the only way the oppressor will stop oppressing, is by resisting. Unfortunately, France did not want to relinquish the power it held over Algeria, which is why the revolution was never going to be peaceful or quiet. There’s no way to make the oppressor peacefully relinquish the power they have. Unfortunately, we’re not in a world where you can just reason with imperialist powers and they subsequently go “oops, my bad, let me give you back your freedom real quick”

Freedom has been bloody and violent and earned by the countless freedom fighters from the beginning of the colonisation until the end of the algerian war, in 1962.

And finally, Algeria got its independence from France on July 5th 1962.

But during the 1940s, all of this was still a vague dream.

The reality Baya lived in was different.

During the 1940s, it was still a common thing for french people to own villas and houses in the algerian colony, and it was still a common thing to hire the natives to be their servants, which is how young Baya found herself as a servant in the house of Marguerite Camina. She did give the young Baya the space to explore her art when she saw how talented she was. Camina loved art and was also an art collector. Therefore, she took it upon herself to give the young girl the opportunities she thought she deserved. Which is all good in itself, but when you dig deeper, I feel like it can get really pervasive. So often, the concept of the good white person who is just here to help the poor person of color who doesn’t know any better. The sources about Marguerite Camina often refers to her as a “fairy godmother” to Baya, who took her and made a shiny little princess out of her (a successful artist). When the truth is that Baya was an accomplished artist in her own right, and the reason she wouldn’t have had access to the opportunities and resources would be because of systemic racism, sexism and imperialism. And because of that, it just.. feels disingenuous to pretend that these factors do not come into play.

Maybe Camina’s motive were really just about loving art and giving a young girl the chances that she wouldn’t have had otherwise, but I do still think that as a white french woman, living in the colonial french algeria, there was a power imbalance and a system in place that is worth thinking about. There is something to say about the white savior complex, about how non-white people and undeveloped countries can only flourish with the help of the benevolent white person. This is truly an example of paternalistic white saviourism colonialist attitudes.

Paris (1947):

During a short stay in Algiers, the gallerist and art enthusiast Aimé Maeght falls in love with her artworks and decides to give her a solo show at Les galeries Maeght. A solo exhibit is the dream of many artists, even when they are accomplished. And yet, Baya had one when she was only 16 years old.

The work she did was so innovative and unique to the parisian artistic circles when she presented her work, that it really did make a very strong impression on many great figures that were really important in the art circles. For exemple, the preface of Baya’s exhibition catalogue was even written by André Breton, one of the main figures of the surrealist movement in France. Her art was very stylistically unique and depicted scenes and elements that were important to the young artist, and the paintings that she produced were very much in line with the surrealist genre, which is why her work had been presented during the context of the Exposition internationale du surréalisme (International Exhibit of Surrealism).

The art she made was also very “algerian” in the way she used traditional algerian ceramics, textiles and patterns as the main inspirations and thematics for her paintings. She uses materials such as watercolor, gouache and ceramics, her paintings are bold and vibrant. The colorful images are inspired by her daily life as an algerian woman, by the world she was living in and experiencing. I think it’s very important to mention that Baya’s work was very Feminine in the sense that it depicted no men. Just women. Her main inspirations have therefore always been women and Algeria. It’s possible to see this as a way to center herself as well as her perspective in a world that often didn’t care for her and her voice, especially as a woman living in a colonized country. Her work was therefore very feminine in that sense. With the world she created, and she created paintings that were imbued w her own unique vision. It was the world as perceived by an algerian woman, and that made it unique and important. In a time when her voice wasn’t listened to, she communicated through her art. The subject of her paintings was always women and algeria, in the most mundane and yet beautiful sense.

Artistically, she also had a very distinctive style that did very much signal the early beginnings of the algerian movement of modern art during the late 1940s, as later said by the algerian writer Kateb Yacine. Her visual aesthetic did stay constant from the beginning of her career until the end of her life. The pictural aesthetic of the women she depicted was far from being figurative, and was more of an abstract representation of people and natural elements that were imbued in her paintings. The colors she used were all vibrants and bold colors, that were often found in natural elements. Burnt oranges and sage greens. Vibrant blues and reds, the colors that are used in her paintings are also ones that are typically used in algerian ceramic work.

When she got married to musician El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine, in 1953, music also began taking a bigger part in the work she was doing, blending in the subjects and thematics that have always been an undercurrent of her work : nature, the traditional arts and crafts of Algeria.

Her paintings were, stylistically speaking, classified as Naive Art, which was the genre that usually designate art created by artists who often lack the classical and formal training. It frequently also describes an art that has a certain kind of innocence and childlike quality and vision to it. This genre is very much often used by artists that are more working class, and do not have the means to afford the formal training, but I have come to see in my research, that this term is often used to refer to non-western, non-white artists, no matter the actual genre of the art they create. Non-white artists are as they often do not have the classical artistic training, or if they are artistically trained, it's not in a way that is often considered like a form of valid training by western artistic circles.

Non-white artists have historically been excluded from formal and official institutions of art, and those institutions still largely remain very much white and the field of art and art history also is. This exclusion of non-white people from those institutions also also further the systemic racism that is in place. It’s just a vicious circle of racism and white euro-centric views being pushed to the front.

The classification of Baya’s paintings as Naive or Primitive art shows a very condescending perspective to non-western art, especially since her art figures firmy within the realm of surrealism and modernism, and not naive art, as shown by the fact that it was presented during Exposition Internationale du surréalisme. It’s true that Baya didn’t have any formal training, which is why going with the strict literal definition, it would be really easy to just classify her work within this genre.

In my personal opinion, I think her work really does fall within the realm of the main art movement of the first half of the 20th century, whether it is naive art, primitive art or surrealism. The work she created was very relevant for the period she was in. Modern art usually is defined by being between 1870 to roughly 1945, even though the dates do change from country to country. I think this can also illustrate another way the world of art and art history is very eurocentric, because the dates for the art movements are usually defined by how they existed within the western world, when the dates don’t quite match up in other parts of the world.

And we rarely talk about how certain art movements existed in non-western countries and the forms they took, for example, the way impressionism was not a movement that only existed in France with the Claude Monet of this world, but also existed in Japan, with artists such as Kuroda Seiki, asai Chu and Kume Keichiro. The way that movement declined itself in Japan was very different from the way it did in Europe, and yet, there’s often no mention of it when we talk of impressionism during art history classes. It’s one of the most recognizable artistic genres, and yet there’s very much a tendency to only stick to Europe when it comes to it.

Baya’s work was also definitely viewed through an orientalism when it comes to the appreciation and analysis of the art she created, and of her as well. I explained more in detail about the concept of orientalism in this article I wrote a while ago (X) but very broadly, orientalism is the way the West views the Eastern Other, and how it creates its own identity by posing it opposing the Orient. The Orient in the western imaginary is an amalgam of including and not limited to north african, arab, indian and chinese cultures, in a sort of Vast Orient. So it’s through this lense that Baya’s art was considered. You only have to read the words André Breton says about her, all very appreciative and effusive, to understand that despite the kind and positive words he uses, it’s also very much orientalist. He uses references to the arabian nights, to her “berber imagination”, to her being the epitome of child-like innocence “with a simple unfragmented consciousness”. So despite the critical acclaim Baya did receive while she was in France, the way her art was viewed was impossible to be dissociated from the fact that it was the art of an algerian woman being shown to a french public.

Atelier Madoura (1948)

It’s in 1948 that the young Baya meets Pablo Picasso at the Atelier Madoura, and history understands that he was so charmed by Baya’s paintings and work that he then went on to work on his series on the women of algiers. But Picasso has become a bit of a controversial figure in art history, in the latest years, and with good reason. As people were bolder in calling out his history of cultural appropriation within the field of Art History, the narrative rightly shifted from Picasso being a genius artist to a white man who profited from the art of non-western artists, specifically from african artists, to further his career. Picasso has made his fortune and his worldwide recognition out of bastardized copies of african art.

I think it’s a very special kind of violence. African art is being devalued, but when it’s made by a white man, it suddenly has value. Several artistic movements of the first half of the 20th were heavily inspired by african and north african artists, while those artists had barely an acknowledgement IF that.

Algiers (1962)

A year after her marriage in 1953, the war for independence started. From 1954 to 1962, a revolution and a war happened to free themselves from the joug of the French Empire. Baya stopped making art at this moment. People do speculate whether she stopped making art to take care of her family, or if it was by solidarity with the independence movement. But needless to say, she didn’t create any art during those years.

In 1962, the algerian people got its independence and sovereignty, away from the ruling of the french. After eight years of war, of fighting for justice, they finally managed to is the year of the algerian independence, but traces and consequences of the french colonization are still being felt to this day, and I do think it will still take a lot of time to unravel the consequences of this colonisation and to heal. Art history, as a field, can be compared to this. It has been created in a very eurocentric perspective and it worked like that for hundreds of years. It’s then logical to think that it will take an equally long time to deconstruct and unlearn in the field of art history. It was built by white people, with a very white gaze upon the world and art.

Art history is a discipline that really does need to be decolonized. On a global level. The perspective that I offer, though, is strictly one of a woman of color who has studied the subject in a superior studies context, in a western country, and who has constantly evolved in a predominantly white sphere when it comes to art history. The art history field that i know is very white, and very western-centric.

In my research, i have seen a lot of articles describing the work of Baya Mahieddine using various words such as “tribal” and “primitive” which .. im .. yeah. Please, let’s not. I think I take issue with this word, because it honestly doesn't mean anything much. It’s the same as using the word interesting when you are trying to describe or critique a piece of media, as it really doesn’t say anything meaningful about the work, but those words do have a very racialized connotation. They say Tribal and Primitive, but what they really mean is “not white” and “seems african”. And yet so often, a deeper analysis of these types of works could be done, and should be done, but these words are very shallow.

I also think there needs to be a whole rethinking of the vocabulary we use to talk and describe non-western art. Words such as tribal, primitive, naive, etc, words that all seem very condescendent and pejorative. A white and western lense through which we view the art we study. There is work that is being currently done on this level but there’s still so much left to be done on this. The gaze of art history is still very predominantly white, whether it’s at the institutional level (universities, museums, etc,) or within the galleries or the publications on art and art history.

The scope of what is prioritized as subjects of interest, is very much set in a very limited, north american and european scope. Maybe, now and then you will find a class that’s being given on non-western art history. During my studies, there were four (4) mandatory classes on the history of canada, and yet no mandatory classes on any kind of non-western art. Even in those classes on canadian art history, we would just go very lightly over the subject of indigenous art history, and very quickly return to focus on the white canadians. The discipline of art history is very navel gazing for white people. It’s the same principle as orientalism, vaguely i guess, in the sense that white culture defines itself in opposition to non-white culture. Non-white art, non-white artefacts and culture is being viewed, not as itself, but as a tool to further define western society and ideals.

When you study art history, people really love to think of the field as “open-minded” and progressive. The reality of it, truly, is that some steps are being taken in a direction to build a more diverse and inclusive discipline. is that it really isn’t. There’s rarely any representation in the professoral corps, and if there is one, it feels very much tokenized. The one professor who is a person of color, often feels like they’re used as a diversity point by the institution. These people are often specialized in a subject that looks relevant to their culture.

And while there's nothing wrong with that and it’s very understandable that one would want to shed light on a specific part of art history that does feel more personal to them, it would be also fun to normalize pocs being profs of all kinds of art history. White people have the scope to be able to study and teach everything, meanwhile it often feels like people of color within the field are stuck in a very specific role. For example, if you have one black professor in your university, that professor will probably be the expert on caribbean art or post-colonialist art. If you have an arab professor ? Here’s your new islamic art professor. It feels very limiting, and it would just be.. yk. Fun. to have perspectives that aren’t your regular white perspective on subjects that have been historically only been told by white voices.

We need to stop putting people of color in convenient boxes for white people to understand, and to only expect them to specialize in a certain field of art history. So often, art historians of color get pigeonholed in a certain subject or specialty. When I tried to apply to the MA in art history, people kept assuming I was going to study something like arab or islamic art, which is all very interesting, but my personal interest lies within the field of illustration in the late 19th century. I wish people wouldn’t have such specific expectations for people of color in the field of art history. The same way that media and art created by people of color shouldn’t necessarily be about their pain, or only focus on their marginality, art historians of color should also not have these expectations set on them.

Unfortunately though, the focus is being given to a very white art history, while completely ignoring the artistic contributions of non-white artists and non-white civilisations. It’s very tone-deaf to teach and praise Picasso without talking about the cultural appropriation and theft he has done of african art and african artists. And yet, this is what we usually face.

It’s really fascinating to know that a woman, a woman of color, can have a wildly successful career in art on a professional level: selling art at a very high price, having solo exhibits, teaching and being recognized during her time as someone who is important within the field of Art. I can give you the example of many women who were successful artists and held great positions during their lives, such as Baya, and Sophie Frémiet and Hannah Höch, and yet I find it so mind boggling how none of that translated to the history books.

Art history, as all histories are, is written, and it’s chosen. It’s very disingenuous to pretend otherwise, that history is something that we stumble upon and that it simply is the way it is, when it has been something that has constantly been written and rewritten with a very distinct perspective in mind.. History is indeed made up of facts. But, it’s important to keep in mind who decides to choose which facts to highlight, what voices to uplift and who is taking up the place. Within the context of art history, which artists and which pieces of art were elevated and showcased, and which ones were ignored. The choices might be unconscious but they’re being made in a very white supremacist environment and are not happening in a vacuum. It didn’t just so happen that white men are the ones who are being remembered later in history, while marginalized people are being forgotten. It’s built into the core system of the discipline (hence systemic racism), and this is why eurocentric views are so prevalent in the way we approach history, and it has been so pervasive, because it’s considered as the neutral view on history, when it is not.

We need to do better.

I do love art history and I do love talking about it in its entirety, the good and the bad, the interesting, the mundane, and everything else. I just hope that the future brings a more open environment to study art history, with a more diverse and inclusive field and that people do feel welcome to get involved in.

Art history, as a whole, is still a very white and closed off to marginalized communities, , and I do hope that the future will show change in a direction that’s more inclusive and diverse, in a way that’s concrete. Words are important, but ultimately are useless without real actions being taken to foster a more inclusive environment when it comes to art history, on every level. Whether it is about the artists, the students, the academics, the critics, the publications, and more . There needs to be an upheaval and reform of the whole entire discipline as to stop centering only a white perspective on art history.

Blida & Algiers (After):

After her marriage, Baya moved to Blida, a city on the outskirts of Algiers, with her family, she spent some years focusing on her family and her children, but after her husband died, she decided to go back to her career as an artist. She continued to create paintings and art after the algerian independence, exhibiting in the National Fine Arts Museum in Algiers, creating art that reflected her and the context she lived in. She also went on to teach at l’École des Beaux-Arts d’Alger (The Academy of Fine Arts of Algiers) during her later years. She continued to make art long after the first exhibit she had in Paris, long after she left the circle of those prominent artists such as Picasso and Matisse and André Breton.

I think it’s very interesting how the french government did try to continue its cultural colonization by trying to poach algerian artists to go to France instead of staying in Algeria. They tried to do that during the algerian war, as well as during what is called the Dark Decade, which were the 1990s in Algeria. A decade of terrorism and fear in the country. And both times, Baya refused to accept that proposition of going to France during these unstable times. She considered herself first and foremost an algerian artist, and she wanted to stay in Algeria.

She died in 1998, after a long life of art and of creation, through the french colonization and through the independence, through all of it. She is remembered by the algerian public as one of its foremost modern artist, and there has been exhibits of her work in Algeria, and a broad, but as much as there has been a renewal of interest for her work, independently of her historical link to prevalent male white artists, I really wish a bigger place was given to non-white artists in art history.

Before we go, I put a bunch of relevant resources on today’s subject in the show notes, you have some books as well as some theses and articles that you can read if you maybe want to further your knowledge and read more on the subject. As always, all the relevant images will also be on all of our social platforms @ imaginarium_pod on instagram as well as on twitter. This podcast was written, narrated and produced, by yours truly, Nadjah, If you want to support this podcast, you can do so on patreon.com-nadjah , n a d j a h . I want to take this opportunity to thank my patrons : may leigh, vilja sala, Trung-Le Cappecci-Nguyen, Jak, Muq, Sam Hirst, Jenny, Jay Harker as well as Nathalie, thank you so much for making the work i do with this podcast possible. On this, I wish you all a very lovely day, evening or night, and I hope to see you soon.

BOULBINA, SELOUA LUSTE. Meet Bazaar Art Cover Star: The Iconic Baya Mahieddine, <https://www.harpersbazaararabia.com/art/artists/meet-bazaar-art-cover-star-the-iconic-baya-mahieddine> 2019.

C. Wakaba Futamura. Cendrillon or Scheherazade?

Unraveling the Franco-Algerian Legend of Baya Mahieddine Women in French Studies, Volume 24, Women in French Association <https://muse.jhu.edu/article/643834 > 2016

https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/30916/Baya-Mahieddine-A-Profile-from-the-Archives

https://www.google.com/doodles/baya-fatima-haddads-87th-birthday

http://www.santetropicale.com/santemag/algerie/digres/baya.htm

https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/baya/

https://bu.usthb.dz/?Baya-Mahieddine-la-charmeuse-de-Picasso-et-Matisse&lang=fr

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/643834

https://www.algerie360.com/baya-mahieddine-la-charmeuse-de-picasso-et-matisse/

http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/bios/Pages/Baya-Mahieddine-.aspx

https://expertise.aguttes.com/estimation-art-contemporain/mahieddine-baya/

https://www.thecut.com/2018/03/the-algerian-teenager-who-influenced-picasso-and-matisse.html

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-algerian-teenager-painted-liberated-women-1940s-paris

https://www.expertisez.com/magazine/baya-l-arabie-heureuse

https://web.archive.org/web/20120411033105/http://www.artdesigncafe.com/naive-art-1992

postcolonialist research

https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2515&context=etd

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0957155817739751

Naive Art :

https://artsandculture.google.com/theme/what-is-naive-art/YwLC8yxnsRUtJA

Interview with Othman Mahieddine, Baya’s son, on djazairess.com website, 3 January 2011.

Sana’ Makhoul. “Baya Mahieddine: An Arab Woman Artist,” Detail: A Journal of Art Criticism. Published by the South Bay Area Women's Caucus for Art, 6/1 (Fall 1998): 4.